Citigroup, HSBC Jettison Customers as Era of Global Empires Ends

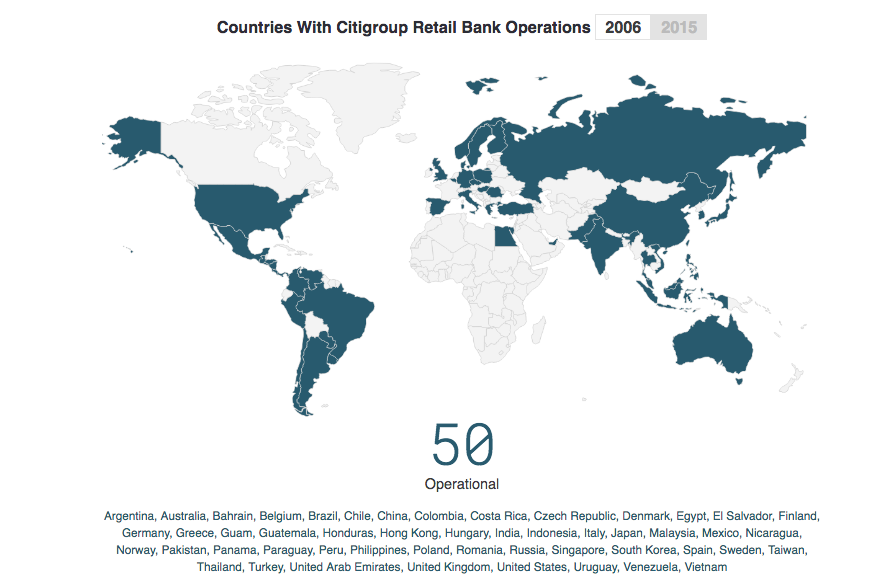

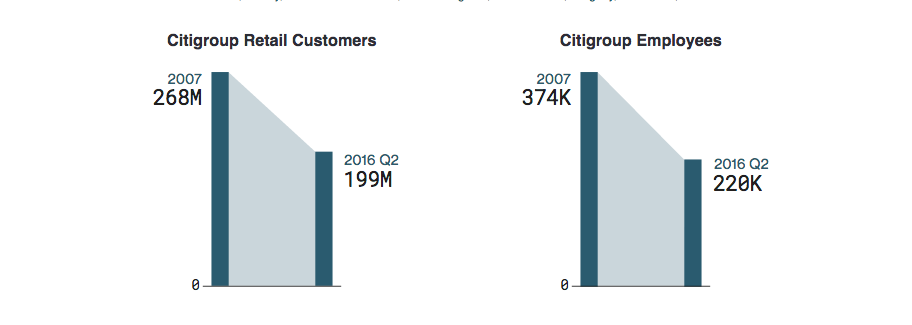

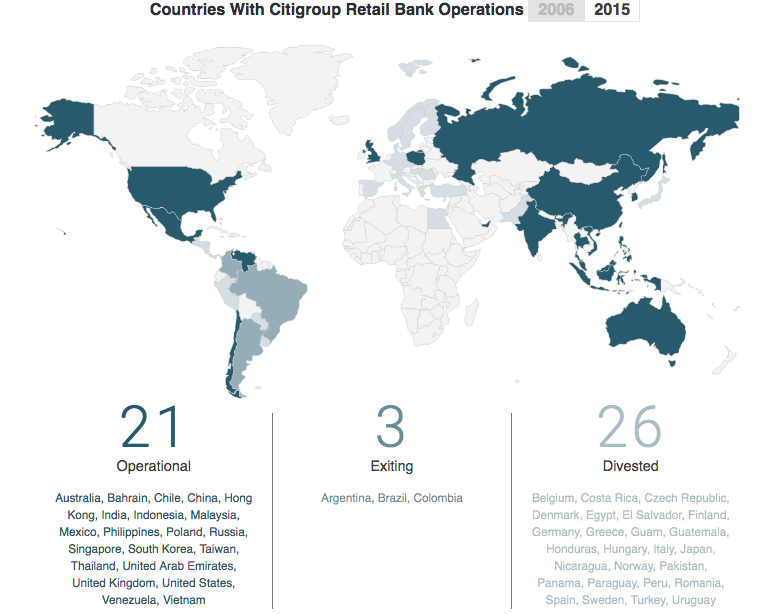

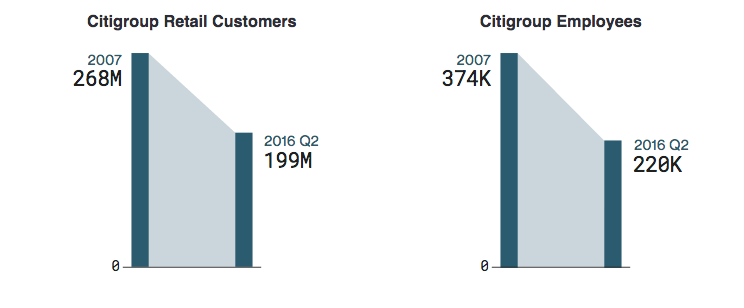

Once upon a time, about a decade ago, the New York-based bank had a global retail empire stretching from Tokyo to Tegucigalpa. It offered consumer banking in 50 countries, covering half the planet’s land mass, and served 268 million people.

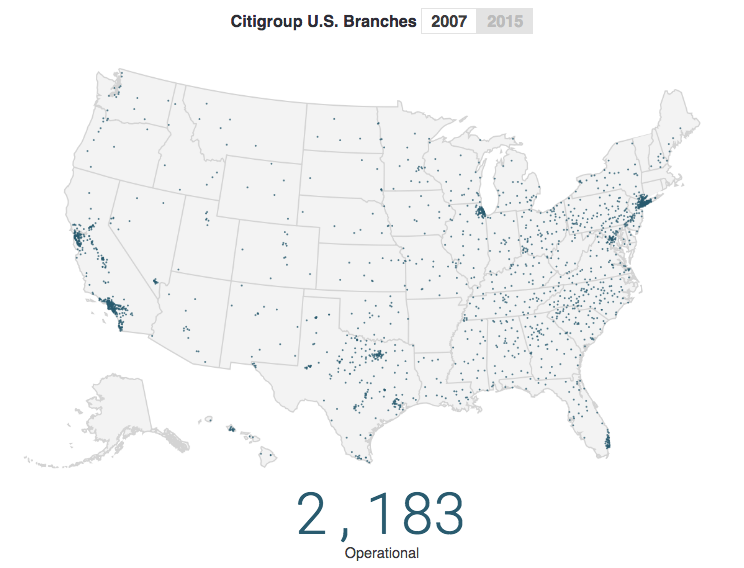

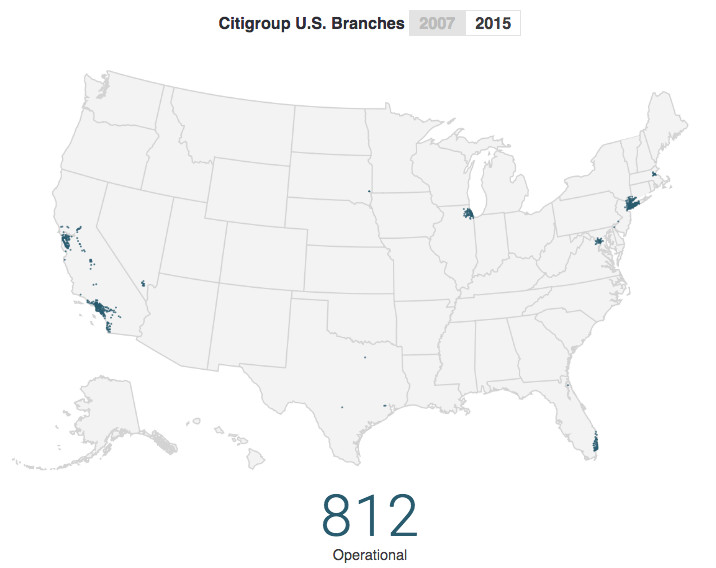

Then a financial crisis, billions of dollars of losses from complicated securities linked to subprime mortgages and a government bailout upended its plans. The bank has since sold or shut retail operations in more than half the countries in which it had a presence, including Guatemala, Egypt and Japan. It reduced the number of branches in the U.S. by more than two-thirds and has gotten out of subprime lending, student loans and life insurance. In the process, it let go about 25 percent of its customers along with more than 40 percent of its workforce.

“Banks are figuring out that providing every product and every service to every client in every country was just wrong,” said Vikram Pandit, who led Citigroup from 2007 to 2012 and used to tout what he called the company’s globality. “So they are unwinding and shedding assets. We’re not close to being done.”

Richest Customers

The transformation of Citigroup, and similar changes at HSBC Holdings Plc and other global banks, isn’t just about cutting expenses. It’s also about looking for greater returns by focusing on the richest customers — high-net-worth individuals, large corporations and institutional investors.

Citigroup says it’s leaner and safer today. But in serving those clients, the bank has bulked up on trading, a business that helped get it into trouble before. It doubled the amount of derivatives contracts it has underwritten since the crisis to $56 trillion. The company, which used to make most of its profit from consumer banking, now gets the majority from corporate and investment banking.

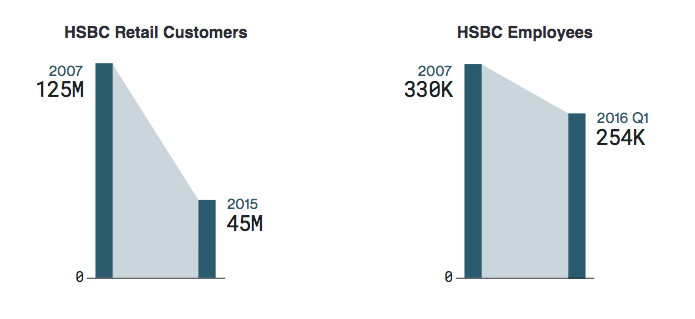

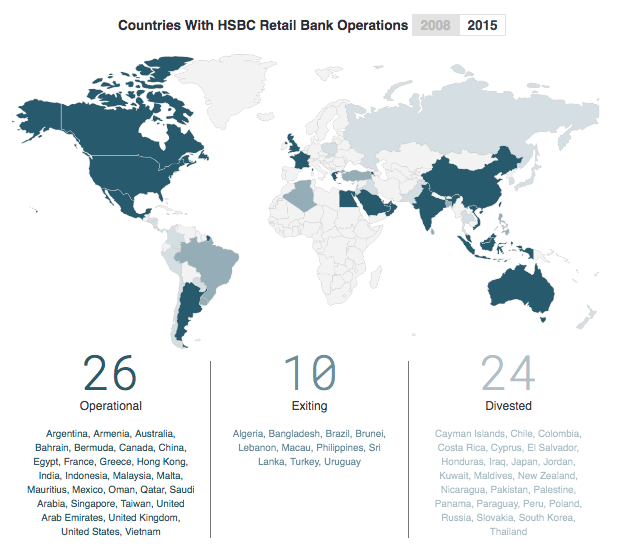

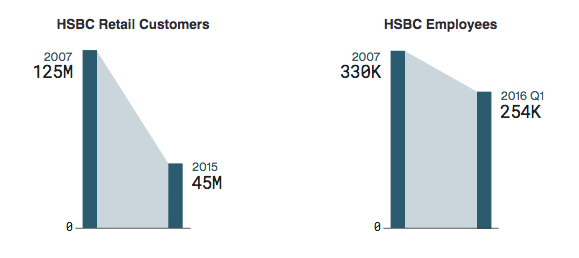

HSBC, which had an even bigger global retail footprint than Citigroup’s and advertised itself as “the world’s local bank,” also has retreated, quitting or planning to get out of consumer banking in more than half the countries it was in and jettisoning 80 million customers. Retail banking’s share of profit has dropped by half as commercial lending and investment banking filled the gap.

Closing Branches

It’s not just a regional retreat. Banks have realized that offering all services to as many customers as possible isn’t a profitable strategy even in the most developed countries. HSBC, based in London, has eliminated 1,600 U.S. locations, including its subprime-lending business, and closed more than 500 branches in the U.K. Citigroup has sold or shut more than 1,300 U.S. branches in the past decade, including its consumer-lending network, to concentrate on major cities.

“We’ve gotten out of businesses where we don’t think that we are successful, and we’ve gotten out of businesses where we don’t see a pathway to getting the types of returns that we think is appropriate,” Citigroup Chief Financial Officer John Gerspach said in December.

HSBC has been using what it calls six filters to determine whether it should exit certain areas or businesses. Among them are profitability, efficiency and risk of financial crime. Spokesmen for both banks declined to comment further.

The cuts in branches and customers haven’t translated yet into increased profitability. Return on equity — 8 percent for Citigroup and 7 percent for HSBC last year — is stuck in single digits, down from more than 16 percent at both banks before the crisis. Increased capital requirements, restructuring costs and low interest rates have eaten into bank earnings. Without the sweeping changes, profitability might have been even lower.

Other global banks are also rethinking their models. Barclays Plc is looking to sell down its business in Africa and has stopped trading stocks in Asia. Royal Bank of Scotland Group Plc, once Europe’s largest lender, has abandoned almost all foreign operations, retreating to its home market in the U.K., and is getting out of most capital-markets businesses. Deutsche Bank AG wants to sell a German consumer bank it bought in 2010 and is cutting back bond trading.

All this retrenchment hasn’t silenced calls to break up big banks. In the U.S., both the Republican and Democratic platforms call for reinstatement of the 1933 Glass-Steagall Act, which separated consumer and investment banking. That would force more radical restructuring at Citigroup and at rivals JPMorgan Chase & Co. and Bank of America Corp.

Turkey Cuts

In most of the countries where Citigroup and HSBC have given up on consumer banking, they still provide corporate services, which require fewer offices and employees. Citigroup boasts having trading floors in more than 80 countries. They also continue to cater to wealthier customers. In some places, HSBC offers online savings accounts, but only to those who deposit a minimum of $70,000.

In Turkey, where Citigroup ended retail banking three years ago, it has kept eight branches and 517 employees to serve corporate clients, down from a peak of 56 locations and 2,349 staff. That enabled it to increase profitability there: Return on equity jumped to 14 percent last year from as low as 1 percent in 2011.

HSBC, which bought a failed Turkish bank in 2001 and turned it into the country’s 10th-largest lender, tried unsuccessfully to sell its unit, which lost more money last year than any of the 46 other banks in the country. It now plans to close half of its branches and focus on corporate clients.

“It’s harder to make easy money in emerging markets these days,” said Hayri Culhaci, vice chairman of Akbank TAS, a leading Turkish lender. “Returns have dropped considerably for all firms, but the largest local banks can use their scale to cushion some of the drop.”

Egyptian Retreat

In China, Citigroup has lost money on consumer banking since at least 2012, a total of about $180 million, according to a local regulatory filing. Meanwhile, in one year, its corporate banking arm there earned twice that amount.

Declining market share helped drive Citigroup out of the retail market in Egypt, where it opened its first branch in 1955, a year before the Suez Crisis. It led a consumer finance revolution there in the 1990s, introducing credit cards and other types of loans.

“They were the best for many years, and among the biggest banks in Egypt,” said Hisham Ezz Al-Arab, chairman of Commercial International Bank Egypt SAE, which bought Citigroup’s Egyptian retail unit this year. “Local banks have learned the business and have invested more and more, becoming competitive with the global banks. Consequently, local operations demand increased attention and direction from headquarters.”

Money Laundering

For HSBC, the biggest risk is violating the terms of a deferred prosecution agreement with the U.S. Justice Department. The bank paid $1.9 billion in penalties in 2012 for its lax oversight of money transfers involving Mexican drug cartels and sanctioned countries including Iran, Sudan and Cuba. Further violations could result in criminal charges and a possible loss of its banking license in the U.S.

Even though it hasn’t given up on retail banking in Egypt, HSBC has been shrinking its operations there. The chief compliance officer in the country has more power these days than the unit’s CEO, according to one person familiar with the business. In Turkey, beset by multiple corruption scandals, the risk is high compared with the meager returns.

“When a country makes up only 2 percent of your assets, and you cannot trust full compliance because there are too many potential risks, you don’t want to stay there,” said Culhaci, who’s been in the Turkish banking industry for three decades.

The risk of fines for money laundering has been a factor for Citigroup too. It paid $140 million to regulators for deficiencies in controls at branches that moved money between Mexico and the U.S. Its Mexican unit, Banamex, is caught up in a fraud investigation involving one of its clients. Citigroup, which gets about 15 percent of its consumer-banking revenue from Mexico, has said it’s cooperating with the probe, is committed to staying in the country and sees prospects for growth.

More Derivatives

-

Even so, Citigroup has been losing market share in Mexico and probably isn’t making enough of a return on its investment to justify staying, according to analysts at Keefe, Bruyette & Woods. They said the bank needs to get out of more countries and businesses and be more aggressive in cutting its assets, which are little changed since before the financial crisis. By doing so, it can lower the amount of capital it’s required to hold as a systemically important institution and return more money to shareholders.

Even so, Citigroup has been losing market share in Mexico and probably isn’t making enough of a return on its investment to justify staying, according to analysts at Keefe, Bruyette & Woods. They said the bank needs to get out of more countries and businesses and be more aggressive in cutting its assets, which are little changed since before the financial crisis. By doing so, it can lower the amount of capital it’s required to hold as a systemically important institution and return more money to shareholders.

The firm has used capital freed up from divestitures to boost its derivatives business, according to Fred Cannon, head of research at KBW. While that might be profitable in the short run, the risks still aren’t well understood, he said. The threat that losses would spread though derivatives contributed to market shocks during the 2008 crisis.

HSBC is refocusing its business on Asia, returning to its roots. The company, founded in the 19th century as the Hongkong and Shanghai Banking Corp., has expanded services in the region surrounding Shanghai, where it sees growth potential in all of its businesses, including capital markets.

“The world’s economy will continue to move to the East,” Stuart Gulliver, HSBC’s CEO since 2011, said in June 2015. “And we’re extremely well-positioned for that growth.”

‘Crony Capitalism’

As the global giants retreat from the retail business, the void has been filled by local banks in developing countries and nonbank financial institutions in developed ones. Egypt’s CIB has tripled its assets in the past decade, while those of Turkey’s Akbank have doubled. In the U.S., car and student loans by specialty finance firms have surged.

One big bank that expanded its consumer business in the U.S. is Wells Fargo & Co. It bought failing rival Wachovia during the crisis, almost doubling the number of branches in its network to 6,236, and expanded in mortgages. But Wells Fargo, which overtook Citigroup to become the third-largest U.S. lender by assets, hasn’t attempted to spread its retail network abroad.

“I just know how difficult it is,” said Richard Kovacevich, Wells Fargo’s CEO from 1998 to 2007 who also ran international consumer operations for Citigroup in the early 1980s. “It’s the culture of the country, the ethics of the country, the close relationships between the banks and the government. Crony capitalism — whatever it is in the U.S. — it’s five or 10 times more internationally.”

While Wells Fargo is the exception when it comes to bank branches, it too has set its sights on corporate customers both in the U.S. and abroad. A decade ago, what it calls community banking made up 75 percent of its profit. Now it’s about half, while investment banking and wealth management account for the rest. This month it agreed to buy a new building in London, enabling it to expand its trading operations in the U.K.

Internet Banking

The focus on wealthier clients and the abandonment of low-income customers has led to a rise in payday lending and online finance. That means people with less-than-stellar credit histories pay too much for loans and mortgages, Kovacevich said.

One reason Citigroup and other lenders are shedding customers and closing branches is that near-zero interest rates have made traditional banking less profitable, according to KBW’s Cannon. When rates were 5 percent or 6 percent, the difference between what banks could charge for a loan and what they paid depositors easily covered the cost of servicing a checking account. Now the math doesn’t work.

“Taking money through deposits in a branch is a money-losing business in the current environment,” KBW’s Cannon said. “Internet banking is less costly.”

Even Goldman Sachs Group Inc., the epitome of high finance, a firm that dealt with only the highest-net-worth clients and the biggest institutional investors, has seen the attraction of internet banking. It started offering online accounts this year for customers with as little as $1. It’s a way to raise cheap funds without incurring the expense of building a banking empire like the ones Citigroup and HSBC once had.

Those days, it would seem, are gone forever.

“Trying to be a bank to everybody everywhere was never a clever idea, but it wasn’t exposed as such until the crisis,” said Stuart Plesser, a senior director at S&P Global Ratings. “Before the crisis, when Citi could function with as little as 1.5 percent tangible common equity, the costs didn’t matter and they felt like they could do anything.”

Additional reporting: Dakin Campbell, Jun Luo, Stephen Morris and Edward Robinson

Research assistance: Laurie Meisler

Graphics: Jeremy Scott Diamond

Editors: Robert Friedman and David Scheer

Photographer: Tomohiro Ohsumi/Bloomberg

First appeared at Bloomberg