The Central Bankers’ Bold New Idea: Print Bitcoins

By JON SINDREU for WSJ

When it comes to bitcoin and digital currencies, central banks might be considering the adage: “If you can’t beat them, join them.”

In a research paper published on Monday, economists at the Bank of England advocated that central banks issue their own kind of digital currency. Using the U.S. as a case study, they argued it could give a permanent boost to the economy of around 3%, as well as providing policy makers with more effective tools to tame financial booms and busts.

BOE economists John Barrdear and Michael Kumhof write that “reductions in real interest rates, distortionary taxes, and monetary transaction costs” would boost the economy.

Much like physical cash, digital currencies like bitcoin allow direct payment from one person to another, but they also have all the advantages of bank transfers, because large payments can be made instantaneously across the globe.

But the main appeal of bitcoin isn’t that it’s electronic. In fact, most money already is: Only about 5% of money in the economy is physical cash; the rest is bank deposits.

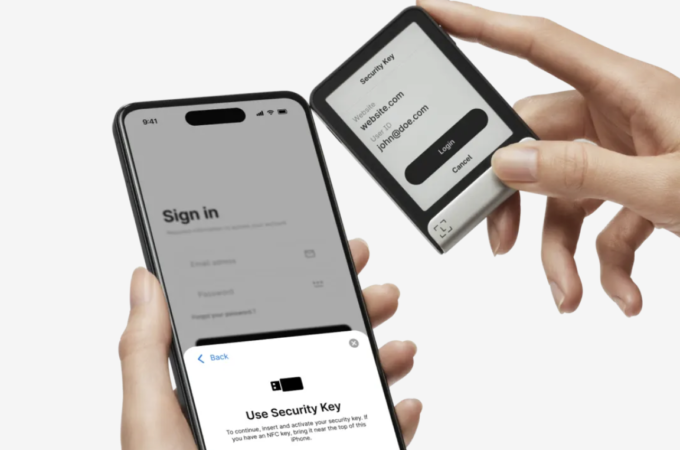

Rather, a digital currency offers a decentralized way to make payments without needing commercial banks to stand in the middle and record the transaction. Payments are validated by other users in a global network of computers and then updated in a shared record known as the blockchain.

‘I don’t see how banks could compete’

—Peter Stella, former central-banking head of the International Monetary Fund and director of Stellar Consulting LLC

Central banks across the developed world, including the Bank of England and the Bank of Canada, are now studying the potential of this technology. Were central banks to issue digital cash and make it available to the general public, money would exist electronically outside of bank accounts in digital wallets, much as physical bank notes do. This means households and businesses would be able to bypass banks altogether when making payments to one another.

This could trigger a radical reshaping of the financial system.

“Making central bank money widely available could have an impact on deposits held at commercial banks and a knock-on effect on the banking system,” the BOE said in a research paper last year, because the new digital money would be seen as a cheaper and safer alternative.

“I don’t see how banks could compete,” said Peter Stella, former central-banking head of the International Monetary Fund and director of Stellar Consulting LLC.

Many economists would cheer at the prospect of all the money in the economy being issued by the central bank, instead of existing as current accounts or deposits, which are the liabilities of private banks. One of the authors of the BOE digital-currency paper, Mr. Kumhof, in 2012 co-wrote research for the IMF making the case for so-called full-reserve banking. He argued it could boost the U.S. economy by around 10%.

Key figures in American economics, such as Irving Fisher and Milton Friedman, have also advocated full-reserve banking. Under such a system, banks are forced to back every single deposit they issue to their customers with money at the central bank, essentially turning the central bank into the sole creator of money.

This isn’t how the monetary system works at the moment. As long as deposits at private banks can act as money, banks have the power to create an infinite amount of money out of thin air: When they grant a loan, banks just use their computers to increase the customer’s account balance.

It’s only when one bank needs to make payments to another that it requires actual central-bank issued cash, called reserves. Banks can always get more reserves at the central bank, for a price.

While this price—the interest rate—can influence how much money private banks create, many economists have long argued this control is too weak, giving birth to financial bubbles.

Proposals to outlaw private-bank money have seen a revival since the financial meltdown in 2008. Iceland is spearheading the charge and studying how to create an alternative system, where all money is created by the central bank.

A central-bank-issued bitcoin would be a means for policy makers to completely control the amount of money in the economy, much like full-reserve banking. That’s not possible right now, because private banks can create money on their own.

For many economists, however, the focus on the quantity of money and who creates it is a mistake. They argue it’s the amount of credit and how it’s used that matters, which means over-optimistic expectations about the future will still bring about a financial bubble.

“It’s the private sector which decides whether actually to accept those terms and conditions and ask the banks to give them the loan,” said Charles Goodhart, a professor at the London School of Economics and former Bank of England rate-setter.

Indeed, the debate dates back to the spat between the Currency School and the Banking School in 19th-century Britain. While the Currency School saw excessive issuance of notes by private banks as the reason for excessive inflation, the Banking School thought the amount of money in circulation was a result of what happened in the economy, instead of a cause.

The idea that controlling the amount of money in the economy will determine economic growth, inflation or credit creation has long appeared false. Since central banks started bond-buying programs in 2008, for example, the amount of central-bank money has exploded, but no inflation has materialized. Experiments to control the quantity of money in the 1980s, inspired by Milton Friedman, also ended in failure, with central banks fully reverting to using interest-rate policy by the 1990s.

Proposals to create a bitcoin-like central bank currency also risk alienating another set of activists: The actual supporters of bitcoin. The whole point of a digital currency, they say, is that it’s money without government.

“The key benefit is decentralization,” said Marco Streng, chief executive at Genesis Mining, a digital-currency company. “The best scenario is where people would not necessarily need to trust the government, they would just need to trust the blockchain.”

First appeared at WSJ