A Physics Lesson for Central Bankers

The world is braced for the discovery of a fifth fundamental force of nature — the four known ones being electromagnetism, gravity, and strong and weak nuclear forces — that subverts the so-called standard model of particle physics. Given the lackluster outlook for global growth, maybe economics needs a similar revolution.

Quantitative easing’s failure to quash the threat of deflation is finance’s equivalent of the bump in the data that alerted physicists to the possibility of a new boson. The mismatch between economic theory and the real-world outcome of zero interest rates poses a direct challenge to the current orthodoxy that puts a 2 percent inflation target at the heart of monetary policy in most of the developed world.

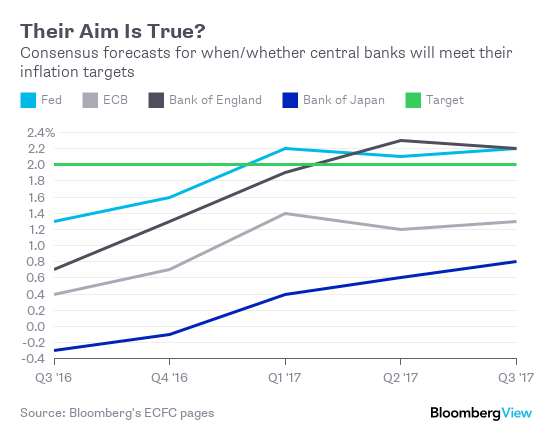

Figures earlier this week showed inflation running at an annual pace of just 0.8 percent in the U.S. and 0.6 percent in the U.K. Consumer prices in the euro zone are rising by about 0.2 percent a year; in Japan, prices dropped by 0.4 percent in June. The consensus forecast among economists surveyed by Bloomberg News is for none of the four central banks in those regions to meet their targets in 2016, and for the European Central Bank and the Bank of Japan to continue falling short for at least the next year:

Years of pumping trillions of dollars, euros, yen and pounds into the economy by buying government debt and other securities hasn’t produced the rebound in inflation that economics textbooks predicted. Record low borrowing costs haven’t led to a surge in investment and spending that would lead to higher prices.

That’s the kind of empirical evidence that should produce a reconsideration of what Rothschild Investment Trust Chairman Jacob Rothschild this week called “the greatest experiment in monetary policy in the history of the world.” Neil Grossman, director of Florida-based bank C1 Financial and former chief investment officer at TKNG Capital Partners, likens the need to abandon the current economic orthodoxy with the impact of quantum physics on science in the last century.

Before Mark Carney became governor of the Bank of England, the U.K. Treasury considered whether it made sense to change the central bank’s mandate, which aims for a 2 percent inflation rate for consumer prices. “We did a lot of work on this in 2012,” Rupert Harrison, the chief macro strategist at BlackRock and former chief of staff to ex-Chancellor of the Exchequer George Osborne, told me earlier this week.

The investigation concluded that raising the inflation target was politically unpalatable, Harrison said. Another potential approach, a switch to targeting nominal gross domestic product growth — in other words, inflation plus growth — rather than consumer prices, is harder to explain to businesses and consumers than a straight inflation yardstick, he said.

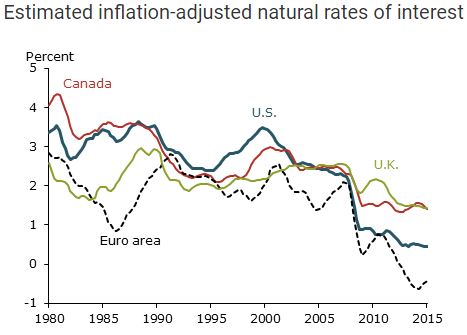

Yet change may be in the air, starting at the world’s most powerful central bank. John Williams, president of the Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco, published an essay earlier this week arguing that the current environment may require a different approach. There’s been a structural decline in the so-called natural rate of interest — the level of borrowing costs that neither stimulate nor hinder growth. Williams included the chart below:

That decline leaves central banks dangerously short of firepower to influence the economy, he wrote:

There is simply not enough room for central banks to cut interest rates in response to an economic downturn when both natural rates and inflation are very low. The underlying determinants for these declines are related to the global supply and demand for funds, including shifting demographics, slower trend productivity and economic growth, emerging markets seeking large reserves of safe assets, and a more general global savings glut.

Williams concluded that central banks should consider either higher inflation objectives or switching to GDP targeting: “Now is the time for experts and policy makers around the world to carefully investigate the pros and cons of these proposals,” he wrote.

“There’s an accumulation of evidence that monetary policy is pretty ineffective,” Nobel prize-winning economist Paul Krugman told Bloomberg Television this week. The comments from Williams are significant because raising inflation targets above 2 percent is “something they have been really, really reluctant to rethink,” he said. “It’s news that anybody at the Fed is even willing to entertain the notion.”

I’ve written before about a theory dubbed Neo-Fisherism that argues for raising rates as a better solution to the current economic backdrop than driving them below zero. Maybe that’s too radical to gain traction. But just as scientists are forced to review their assumptions when the experimental evidence undermines existing theories, central bank economists should acknowledge that the world isn’t responding to their guidance in either the way they expected or how they would want it to. In short, a new approach to monetary policy is needed.

To contact the author of this story:

Mark Gilbert at magilbert@bloomberg.net