Big Banks Turn Silicon Valley Competition Into Profit

In an annual letter to shareholders last year, JPMorgan Chase & Co. Chief Executive Officer Jamie Dimon warned in bold print that “Silicon Valley is coming” for the financial industry. This year, his tone was upbeat, describing payment systems and partnerships his bank set up to compete.

“We are so excited,” he said.

Predictions that banks are about to be disrupted by tech-driven upstarts are starting to look a bit like LendingClub Corp.’s stock. The online loan marketplace’s value soared in late 2014 and has since slid more than 80 percent. Banks including JPMorgan, Goldman Sachs Group Inc. and American Express Co. are finding all sorts of ways to profit from such challengers — via partnerships, funding arrangements, dealmaking and, sometimes, mimicking their ideas.

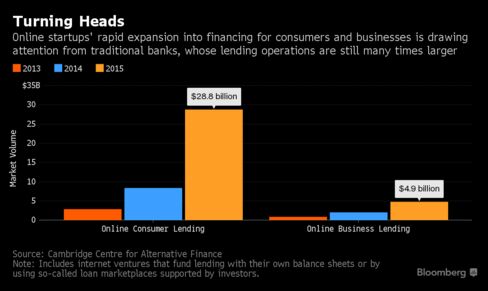

It’s not that the upstarts — often called fintech — are failing to gain traction. Internet ventures pitching loans to cash-strapped consumers, small businesses and home buyers, for instance, have posted spectacular growth in recent years. It’s just that banks have a huge lead in lending and are watching the startups closely. As borrowers embrace new services, traditional firms are riding along.

Here are five examples:

LendingClub’s Backers

Few companies embody the promise and changing fortunes of fintech like LendingClub. It pioneered peer-to-peer loans during the financial crisis, matching consumers looking to borrow cash with people looking to make a profit on interest. Big investors soon realized there was money to be made. Local banks snapped up loans for their own balance sheets, cutting costs and diversifying beyond home markets.

In May, LendingClub broke out its sales to banks: Community banks and other old fashioned lenders snapped up about 34 percent of the $2.8 billion of loans it arranged in the first quarter, up from an average of about 25 percent during 2015.

Investment banks Goldman Sachs and Jefferies Group also bought loans to bundle into securities this year, a process that stalled when LendingClub’s founder stepped down amid internal reviews. But that’s not all.

Some of LendingClub’s biggest loan buyers have bolstered their war chests or operations with financing from banks. Colchis Income Advisors entered into a credit agreement with Bawag PSK of Austria, according to regulatory filings. Arcadia Funds arranged for two of its Cirrix partnerships to borrow from Silicon Valley Bank. And MW Eaglewood lined up financing for its main LendingClub fund from Capital One Financial Corp. in 2012. Spokesmen for the funds and banks declined to comment or didn’t respond to messages.

Goldman Sachs, meantime, is looking to compete. The bank has announced plans to roll out a consumer lending platform. The firm is keeping mum on details like rates and terms until the service debuts this fall, but finance chief Harvey Schwartz predicted this month that it will be “a durable business” for the company.

Chasing Entrepreneurs

Small businesses can thank internet ventures for simplifying loan applications, speeding decisions and providing much-needed credit when many traditional banks were pulling back in the wake of 2008’s financial crisis. Nonbanks now provide about one-quarter of the $800 billion in loans outstanding to the sector, according to researchby QED Investors and Oliver Wyman. But the interest rates aren’t always low.

For a time, banks were content backing the loans. Goldman Sachs was among firms that entrusted more than $300 million years ago to fund lending by On Deck Capital Inc., one of the largest providers of small business loans over the internet.

Now, established lenders are taking a more active role. JPMorgan announced a deal in December, letting it access On Deck’s proprietary credit-scoring system to quickly evaluate applicants before using its own balance sheet to make loans. On Deck, in turn, gets a foothold in the burgeoning “fintech as a service” market. But the arrangement has done little to stop a 49 percent slide in the company’s stock this year.

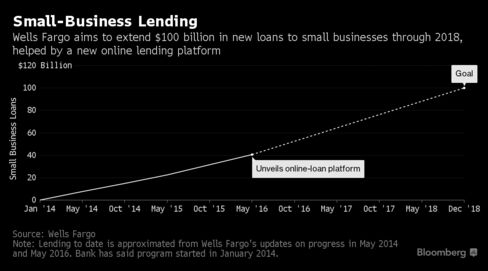

More recently, established lenders have announced their own online lending portals for entrepreneurs.

Wells Fargo & Co. said in May that its new “fast decision” platform will help it reach a goal of providing $100 billion in new loans to small businesses by 2019. AmEx, which already provides more than $200 billion of funding to entrepreneurs for business purchases on their credit cards, expects a new online-loan portal will let it handle even more of their spending.

Mortgage Apps

Fintech ventures starred in Super Bowl ads this year, with Quicken Loans toutingRocket Mortgage, a platform letting users apply for home loans on smartphones. The narrator imagined it setting off a “tidal wave of ownership,” spurring demand for kitchen appliances and furniture, and sending the economy into the stratosphere.

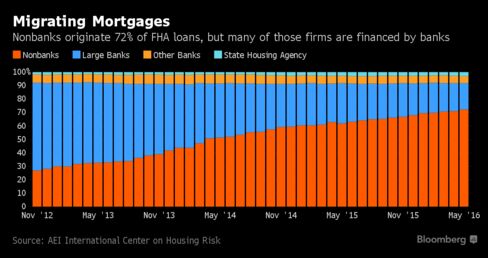

Less than a decade ago, the financial crisis took a huge toll on nonbank mortgage lenders that once gorged on fees from originating loans and selling them to the securities market. Now the sector is booming anew, accounting for more than than 70 percent of Federal Housing Administration loans as of May. (Unlike before, their loans are designed to meet the FHA’s strict rules.) Quicken ranks as the No. 2 U.S. mortgage provider behind Wells Fargo.

The tidal wave is benefiting banks, too. Behind the scenes, many of the upstarts get support from traditional banks. Detroit-based Quicken, for example, raised $1.25 billion for itself and its parent company last year in a bond sale underwritten by JPMorgan and Credit Suisse Group AG. It also used lines of credit from banks to help close $80 billion in home loans that year.

And such arrangements may be the norm, according to a March report by the Government Accountability Office examining the role nonbanks play in servicing mortgages. In interviews with 10 firms, it found most use credit lines to fund operations, including originations.

Bitcoin, Blockchain

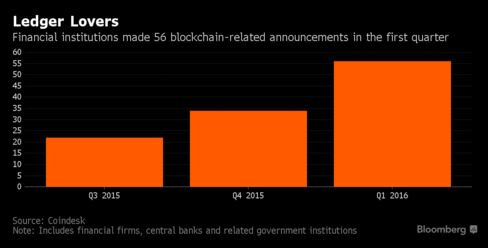

Early bitcoin enthusiasts set out to make cash, credit cards and the entire financial system obsolete. Instead, the public ledger that verifies and records bitcoin transactions, known as the blockchain, may help burnish Wall Street profits.

Banks, industry groups and related startups are looking to use blockchain’s innovations to speed trading, money transfers, record keeping and other back-end functions. More than 50 of the world’s biggest banks have joined the R3 consortium to help design a financial-industry ledger and develop ways of using the technology.

That excitement helped blockchain startups lure more venture capital than their brethren trying to capitalize on bitcoin during this year’s first three months, the first time that’s happened, according to industry tracker CoinDesk. Startups include Digital Asset Holdings led by Blythe Masters, who once ran JPMorgan’s commodities business and helped pioneer credit-default swaps. She has enlisted financial support from banks to create ledger-based software changing how they trade a variety of assets.

For all the hype, blockchain has yet to achieve broad commercial adoption. But for banks, there’s high pressure to innovate: They’ve had to slash headcount amid a prolonged trading slump, stiffer capital rules and increased compliance costs. Banco Santander SA’s venture arm estimated last year that blockchain could save financial firms $20 billion a year in settlement, regulatory and cross-border payment costs.

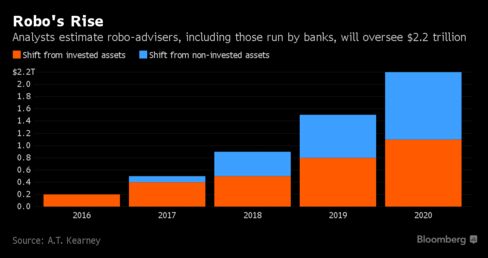

Brokers are so 2011. In the past half-decade, technology startups have popularized so-called robo-advisers — algorithms that help retail investors (mainly millennials and penny pinchers) build and manage portfolios with little or no human interaction. The industry has seen dramatic growth, from almost zero in 2012 to a projected $2.2 trillion in assets under management by 2020, according to a report from A.T. Kearney.

Top Wall Street firms, seeking stable fee income, are now developing their own robotic arms. Bank of America Corp. will unveil an automated investment prototype this year after assigning dozens of employees to the project in November, people familiar with the matter told Bloomberg at the time. Morgan Stanley and Wells Fargo also have said they would build or buy a robo-adviser.

Ally Financial Inc. purchased TradeKing Group Inc. for $275 million to increase its online investment offerings. That deal included an online broker-dealer, a digital portfolio-management platform, educational content and social-collaboration channels.