Insurance Companies Have Joined the Ranks of Shadow Banks

When all else fails, lend.

That’s the strategy of some of the biggest U.S. insurers as they seek higher returns in an investment universe where buying bonds sometimes means guaranteed losses.

The largest U.S. banks are constrained by post-2008 rules that make it tougher for them to extend loans. So companies such as MetLife Inc. and American International Group Inc. are grasping more market share. While many insurers have been in the commercial real-estate market for decades, the industry is branching out into home mortgages, small-business lending, car loans, renewable-energy financing and student debt.

“There’s no question that insurance companies are looking to diversify into new areas and innovate as much as possible,” said Adam Hamm, North Dakota’s insurance commissioner who serves on the U.S. Financial Stability Oversight Council.

The quiet reshuffling of the lending industry is part of the transformation of American finance following the 2008 credit crisis. Together with hedge funds, private equity shops and tech startups, insurance companies have joined the ranks of shadow banks — firms that act like banks without being regulated like them. Lawmakers and regulators have taken notice of the changing landscape, with Democratic presidential nominee Hillary Clinton promising to “tackle financial dangers” by enhancing transparency and reducing volatility in the emergent system.

Different Standards

Insurers are becoming the new financial supermarkets in part because traditional investments offer minuscule returns — 10-year U.S. Treasury notes yield less than 1.6 percent while some European sovereign debt is negative, meaning investors pay to park their money there. And pushing into more aggressive investments, such as hedge funds, tied up too much capital and resulted in losses in recent quarters.

AIG Chief Investment Officer Doug Dachille said the ventures only make sense for companies with scale because it requires more staffing to originate the loans. “Given the lack of liquidity in the securitized markets, which is how many insurers have previously purchased loans, insurers are now waking up to the reality that it’s better to own the loans directly,” he said.

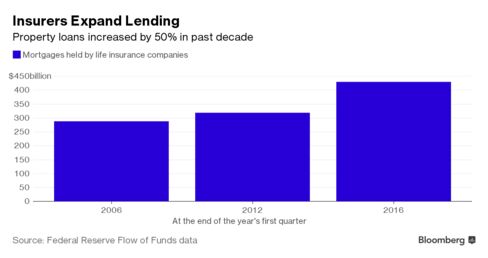

Insurers are now responsible for 11.6 percent of the loans in the global private debt market, which includes direct lending, according to data provider Preqin. Firms boosted mortgage funding by 50 percent to $430 billion in the last decade, according to the Federal Reserve.

In 2015, MetLife, the largest U.S. life insurer, made more property loans than it ever has in its 148-year history. Chief Executive Officer Steve Kandarian said the company plans to keep expanding in 2016 because mortgages have “predictable income streams.” MetLife declined to comment. AIG has more than $20 billion allocated to commercial mortgages and is increasing its wager as it pulls out of poorly performing hedge funds.

TIAA, led by Roger Ferguson, is the world’s largest investor in private debt, Preqin said. TIAA has also hired ex-Carlyle Group LP money managers to create a venture focused on lending to middle-market companies. A TIAA representative didn’t respond to requests for comment.

Babson Capital, owned by Massachusetts Mutual Life Insurance Co., raised more than $2 billion for direct lending, Preqin said, among the biggest efforts this year. A spokesman for Babson and MassMutual declined to comment.

Federal Reserve

Regulators have traditionally focused on insurers’ securities-lending and repurchase agreements. U.S. insurance companies are regulated by the states. AIG and Prudential Financial Inc. are overseen by the Fed because they’ve been designated systemically important financial institutions. MetLife won a court battle to avoid that designation, and General Electric Co. closed its finance division, in part to escape greater regulatory scrutiny. GE sold off more than $100 billion of its assets and some insurers won business in industries that GE left behind. A Prudential spokeswoman declined to comment.

Last month, the Fed proposed capital rules for insurers more appropriate for their longer-term liabilities. Proposals by the National Association of Insurance Commissioners will make commercial mortgage lending more attractive for insurers in the next two years relative to corporate debt, according to Mark Snyder, the head of institutional strategy and analytics at JPMorgan Chase & Co.

Insurers can provide lower-cost alternatives for borrowers, said Mike Coster, chief executive officer of financial services firm Kimberlite Group. Five years ago, a traditional lender might charge 14 percent for mezzanine debt; that product today is about 9.5 percent, he said. And while the pricing is more competitive, insurers aren’t loosening the terms of the loans, Coster said. S&P analyst Deep Banerjee said default rates from the loans tend to be low due to strict underwriting.

Insurance companies are looking increasingly like asset managers. MetLife, MassMutual, Prudential and New York Life Insurance Co. are building units that invest client funds rather than just the cash they hold to back policyholder obligations. A New York Life spokesman declined to comment.

Joint Ventures

The data show only part of the expansion. Insurers have also formed joint ventures, invested in private equity funds that lend, or acquired lending companies, giving them stakes without carrying loans on their balance sheets.

Athene Holding Ltd. owns parts of a home-loan company, a health-care-industry lender and a commercial mortgage firm. An Athene spokeswoman declined to comment. A division of Babson agreed to buy a commercial lender this year.

While insurers are viewed as safe lenders because they can deploy funds for a long time and don’t have to worry about depositors withdrawing money at a moment’s notice, they may not have the loan-underwriting expertise of longtime lenders, said Yariv Itah, an asset-management adviser at Deloitte Consulting.

And there are cautionary tales, such as loans tied to bankrupt retailer RadioShack Corp., which wiped out first-quarter profit last year at insurer Fidelity & Guaranty Life. An FGL spokesman declined to comment.

“There’s the risk of not knowing exactly how to do this,” Itah said. “So whenever you have an investor wading into a new area of investing, there’s some operational risk.”

First appeared at Bloomberg