India’s Audacious Plan to Bring Digital Banking to 1.2 Billion People

By Saritha Rai for Bloomberg Business

A biometrics-backed ID system will make it easier for everyone—from rural villagers to urban dwellers—to ditch cash.

India is trying to yank its cash-based economy into the 21st century.

But how do you get 1.2 billion people, many of whom have never seen a bank or opened an account, to send digital payments to each other?

The government’s answer is an effort it has named the Unified Payment Interface. Debuting Monday, it’s a system designed to make transferring and receiving money as easy as exchanging e-mail or text messages.

The goal is to bring banking and financial services to hundreds of millions of citizens, many of them poor and disadvantaged, in one fell swoop. The network was created by India’s retail banks and backed by India’s central bank—and they’re confident it will work because it’s built on top of an even more audacious project: India’s biometrics-enabled national ID system, called Aadhaar after the Hindi word for foundation.

So far, India’s attempt to assign every citizen a unique 12-digit number associated with a person’s unique iris, fingerprint or facial features, is succeeding—just last week, Aadhaar reached its milestone of registering 1 billion people. With more than 80 percent of Indians enrolled, it gives the payments system a solid base to build on.

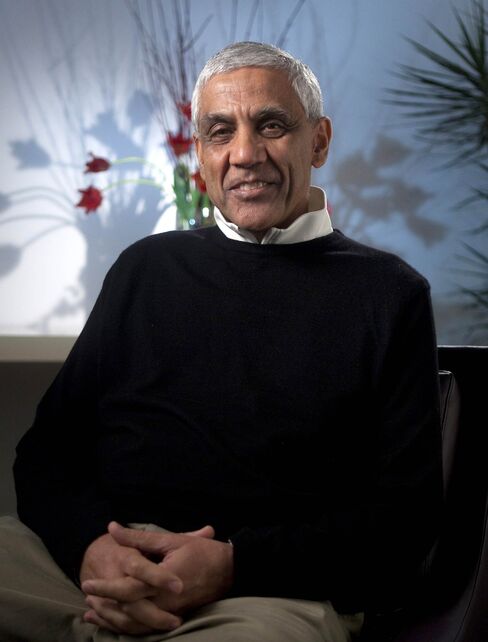

“The interface will bring banking to the unbanked,” said Vinod Khosla, billionaire investor and co-founder of Sun Microsystems. His Bangalore-based incubator Khosla Labs is backing an Indian startup called Novopay, which offers mobile banking at 44,000 kiranas, or neighborhood convenience stores, in the country.

More than 233 million Indians have never been to a bank, and most accounts have a balance of zero, according to PricewaterhouseCoopers. And even though India has the world’s second-biggest population, there are only about 23 million credit cards in the country, according to the Reserve Bank of India.

India is hoping to replicate the success of a similar digital-payments scheme in Kenya. Introduced in 2007, Safaricom’s M-PESA system lets people send and receive money via mobile phones. What’s impressive is the sheer number of people doing so: 22 million, or half the African country’s population. India’s system is designed to work at a more basic level, with payments flowing between mobile, banking and other networks.

That also means mobile banking’s growth potential is huge. India has the world’s fastest-growing smartphone market, which is projected to double in a few years from the current 220 million users. Soon, all it will take in India to send money is a phone number, an Aadhaar number or a simple virtual-payments address.

“The robust system will help India leapfrog the desktop and the credit-card economy to become a mobile-first economy, accelerating e-commerce and driving a host of financial services,” said Nandan Nilekani, who led the push to introduce Aadhaar and has been advising banks on the rollout of the new payments network.

The main challenge will be cost. In order for India’s new digital payments system to succeed, transaction fees will have to be set very low in a country where the average monthly wage is about $300. While the network’s backers say costs will come down, detractors said the banks will have to keep fees affordable. Success will depend on the combination of banks, startups, user experience and digital literacy, said Akanksha Sharma, senior analyst at research firm GSMA Intelligence.

Srikanth Nadhamuni, chief executive officer of Khosla Labs, said the best way to think of the project is by comparing it to how shampoo was introduced in India. Decades ago, most people couldn’t afford to buy an entire bottle of shampoo, so Unilever, Procter & Gamble and other companies sold them in small sachets that people could afford to buy, paving the way for marketing everything from detergent to toothpaste in rural areas. Nadhamuni is betting that the new digital payments system will be be low-cost, high-volume, like a “shampoo-sachet revolution in the financial sector.”

Flipkart, India’s biggest online retailer, is getting in on the action. The e-commerce leader recently bought PhonePe, which is building a mobile application based on the Unified Payments Interface. The app will let Web shoppers pay for goods, daily wage workers manage bills and help migrant workers send money home—with just a phone number.

“UPI has the potential of transforming the entire payments ecosystem in the country,” said Binny Bansal, Flipkart’s co-founder.

The article first appeared in Bloomberg Business