Tokenised funds to reshape PE/VC fundraising

Initial coin offers (ICOs) and the emergence of tokenised funds — represented by the issue of equity tokens — are set to reshape the dynamics of how private equity (PE) and venture capital (VC) fund managers raise capital, bringing greater transparency and democratisation to the fund management space.

Equity tokens, also known as security tokens, are tokenised securities which derive their value from an external, tradeable asset and are subject to securities regulations. In Singapore’s case — given its status as the largest centre for ICOs in Asia as at 2017— such securities products fall under the remit of the Securities & Futures Act (SFA).

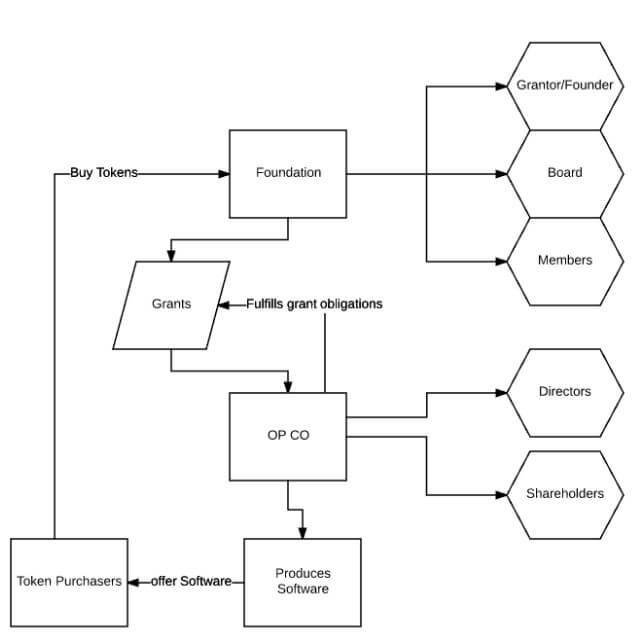

The Monetary Authority of Singapore (MAS) currently notes that digital tokens can function in the role of a utility token that offers benefits in the form of goods or services, or an equity token that operates as an offer of shares, units in a collective investment scheme or a debenture; current regulations require issuers of security tokens to lodge a prospectus with the MAS, with online exchanges that facilitate their trading requiring approval.

The use of equity tokens serves to disintermediate the use of private placement agents, who often serve as intermediaries between the various limited partners (LPs) — foundations, endowments, family offices, trusts, corporates, fund of Funds (FoFs), insurance firms, state funds, pension funds and other players — and the fund managers that look to engage them.

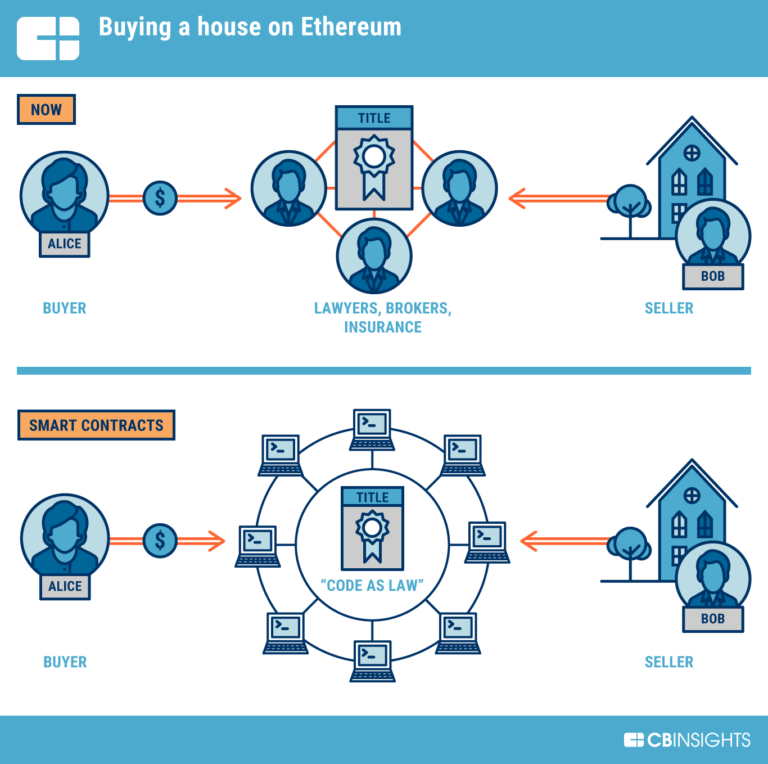

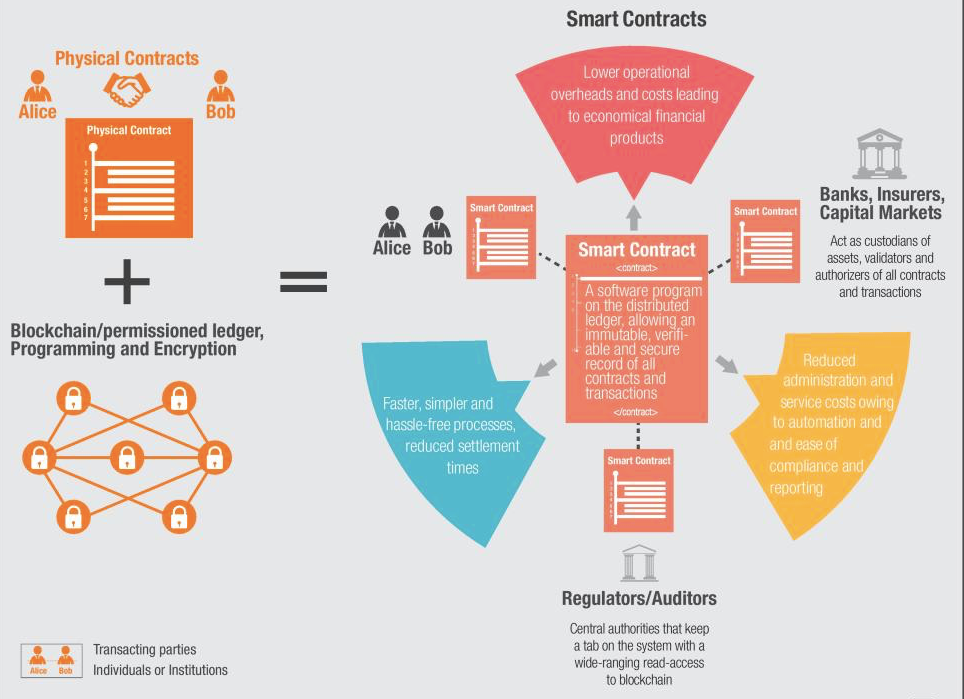

An additional layer of protection that the use of equity tokens in an ICOs could offer is the use of smart contracts, as exemplified by the Ethereum blockchain. Fundamentally, it offers a decentralised and more democratic tool for fund managers to raise capital.

Tokenised venture funds

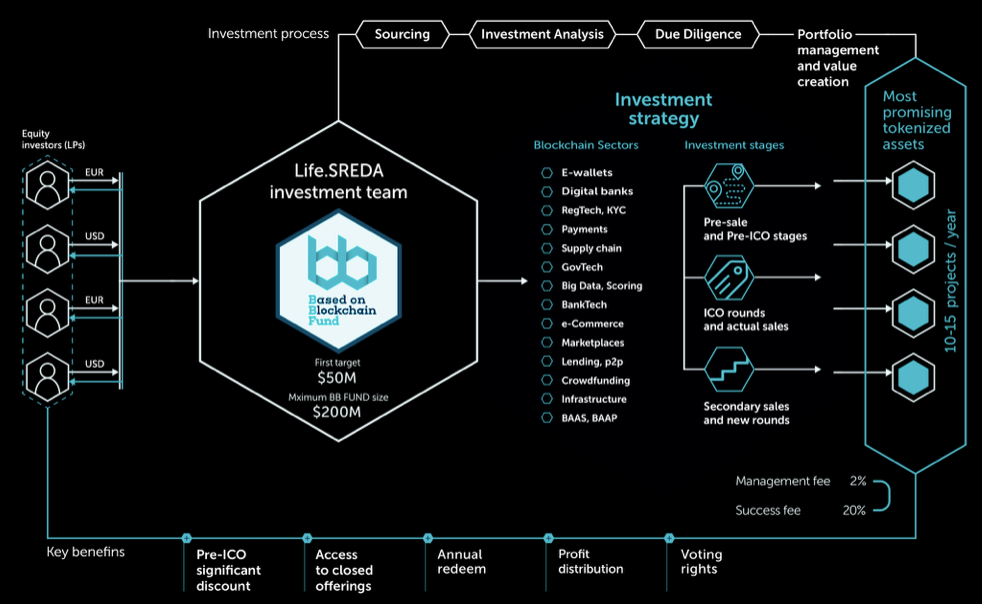

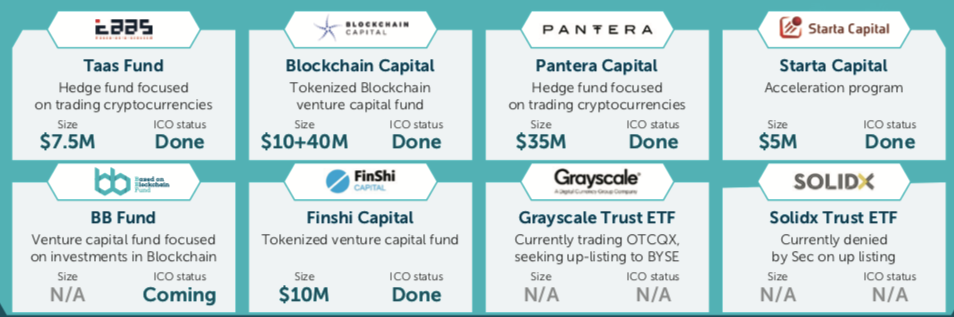

In Singapore, the Based on Blockchain Fund (BB Fund), whose launch was announced by LifeSREDA.VC in May 2016, is planning to conduct an initial coin offer (ICO) in Singapore. This could make it the first fund based out of Southeast Asia to raise funds through a security token sale, which has emerged as a new financing option for startup ventures, as well as offering benefits to both LPs and fund managers in terms of transparency and democratisation.

Silicon Valley venture capital firm 500 Startups has also entered the space with its 22X Fund, which is jointly operated with Securitize Capital LLC. This vehicle permits accredited investors who purchase 22X tokens to own up to 10 per cent equity in the 22nd batch of its portfolio companies.

Companies that form this particular fund have collectively raised over $20 million, with financial backers including institutional investors such as 500 Startups, Accenture and Deutsche Bank. The 22X Fund aims to raise up to $35 million which will be deployed immediately and invested on a pro-rata basis in the equity of participating early-stage ventures.

Investors in this fund can purchase 22X tokens with Bitcoin, Ethereum, USD or other currencies, with the tokens enabling ownership of up to 10 per cent in each participating firm. Proceeds from the fund are distributed pro rata to participating companies capped at $1 million, with token holders able to trade tokens after a year and receive proceeds from liquidity events.

Meanwhile, two organisations in the Indo-Asia Pacific (IAPAC) which have engaged in ICOs to raise capital for their funds are Starta Accelerator, which raised $5 million, and Finshi Capital, which raised $21.4 million. Such developments come at a time when venture capitalists in the city-state are worried about its impact on their sector.

The BB Fund — which has not issued tokens to date — is aiming to raise a corpus of $200 million, with its first close at $50 million. It plans to concentrate on enterprises operating in the blockchain and financial technology sector. It will target investments at the pre-ICO (pre-sale), ICO, as well as pre-seed, seed and Series A funding rounds, with an investment cycle of three years.

The BB Fund will be issuing the BB Token and has capped its supply at 1 million tokens priced at $200 and fixed in Ethereum (ETH), with investors able to trade tokens on the funds’ trading desk during the annual redemption period. According to the funds’ website, the BB Token represents the share of investor’s ownership in the BB Fund and is “collateralised by a portfolio of underlying tokens”.

In an email exchange with this portal, Igor Pesin, the CFO of BB Fund and LifeSREDA’s investment director, explains: “While we see several ICOs made by investment funds, most of them are not using equity token (meaning positioning it as a security) and do not follow the regulatory rules, related to securities. During such fundraisings even necessary KYC, risk assessment and compliance procedures (AML, CTF, PEP checks) are usually are not executed, and the source of funds and source of wealth assessment are never done, which are obligatory in dealing with securities.”

He adds, “Equity tokens are just starting to appear on the market and mainly introduced by already established and experienced players because this is much more complicated and demanding approach than fundraising via utility tokens.”

According to Pesin, the use of equity tokens raises legal complexities in terms of raising a fund in a jurisdictions like the US or Singapore, where ICOs can fall within the remit of the SFA if the ICO deals with a securities product, particularly with regard to due diligence elements such as KYC (know-your-client), AML (anti-money laundering), CTF (counter-terrorist financing) and PEP (politically exposed person) checks.

Raising a fund in Singapore also comes with regular internal and external audits, as well as additional requirements for information disclosure.

As for the liquidity options of LPs? Pesin elaborates: “Investors in those tokenized funds, which are structured in a proper and compliant way, get the same rights as in a classical limited partnership, meaning they own a share of underlying assets in the fund. Regarding the liquidity, they have several options for selling their equity or tokens to another accredited investor, they can redeem their stake or they can just wait for profit distribution after each successful exit.”

Fundraising dynamics

Goh Sze-Hui, a corporate partner in Eversheds Harry Elias,whose practice areas cover cross-border mergers and acquisitions, joint ventures, corporate finance and corporate restructuring, see’s the ICO phenomenon as a fluid and evolving space given its relative youth.

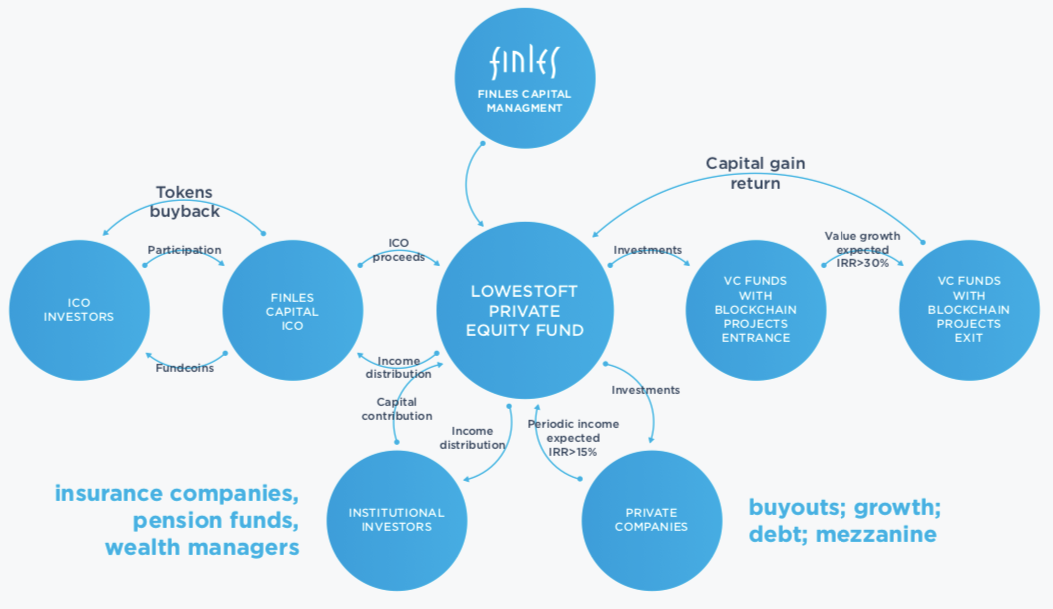

Asked for her take on issues surrounding the FundCoin ICO of the Dutch asset management firm Finles Capital — which would have been the first ICO by a private equity fund but was eventually suspended — Goh tells this portal that the matter highlights key points private equity players need to be aware of.

She explains: “Firstly, there is the question of choosing the jurisdiction for an ICO. As the article states, for example, many ICOs actively seek to exclude US investors, and for many ICOs this can be a reflection of (i) a lack of financial means to back an ICO in certain countries, and (ii) a lack of understanding of the relevant regulatory regime, and so a desire to exclude it.”

“Less common, however, as an option that should be seriously considered when performing an ICO, is whether to, instead of listing countries where an ICO is excluded, rather list the countries where the ICO is to be performed. This would allow the ICO provider to properly consider the framework where they are providing the ICO, and, since as a general rule of thumb marketing / financial promotion rules which apply are those in the country where the token is sold, makes it easier to be sure tokens are sold in compliance with all applicable regulation.”

“Secondly, and following on from the above, most countries will have a local regime for protecting investors. Therefore, just excluding investors from certain countries from investing does not equate to being able to do whatever you want in and ICO. Generally, all countries, for example, have rules against fraud and misrepresentation, which apply regardless of whether an activity is a so-called “regulated activity” or not.”

The growth of ICOs has also seen the emergence of platforms like Waves and CoinLaunch, which aim to simplify the ICO process and enable businesses to issue their own digital tokens and manage their ICOs.

Goh believes that such platforms are beneficial to both regulators, investors and entrepreneurs. She says, “These platforms can form a dual purpose. They can both facilitate the ICO process, as well as provide a validation mechanism (i.e. only ICOs of a certain quality may be accepted on a platform). As such, they are like to become increasingly popular as they form a framework beneficial to both the investor and the entity launching the ICO.”

“They also provide a natural hub of experts, who can then engage with regulators when developing the regulatory framework, as well as a mechanism for regulatory enforcement of that framework, as parties can be blocked from accessing the platform if they do not meet prescribed requirements. The exact end result if, of course, uncertain, given the nascent nature of these platforms, but there is definite potential form them to play a significant role ahead.”

Meanwhile, Robin Lee, the CEO of HelloGold — a startup which closed a $4 million venture investment and raised capital from an ICO — and former CFO of the World Gold Foundation, opines: “As long as you adhere to existing regulations, I think in many ways it can have a lot of benefits, the most obvious being safety and transparency as you can democratise fundraising.”

“Traditionally, LPs write cheques to the VCs, but equity token sales give a broader pool of people a chance to gain exposure to the venture capital asset class and for VCs to raise more capital. That’s the theory anyway. Realistically, VCs fund managers will have to follow securities regulations regarding fundraising in the jurisdictions they are based in, which remain unchanged.”

He adds, “While I’m not sure of the benefits it would bring to the table, theoretically because of its blockchain basis and smart contract governance, it’s more transparent. If you’re a new fund trying to raise money, it may be an easier approach.”

Lee observes that while tokens have enabled investors to enjoy more rapid liquidity, he also notes that its possible for people to purchase tokens that cannot be redeemed for up to five years.

“If VCs were to raise funds and then focus on a non-traditional space, that makes a lot of difference; it depends on the rules that fund managers establish on the smart contract. The liquidity option for VC funds can see them liquidate in a month but pay it out in five years. The security token for your fund could the funds you’re allocating being frozen for the next five years before being redeemed.”

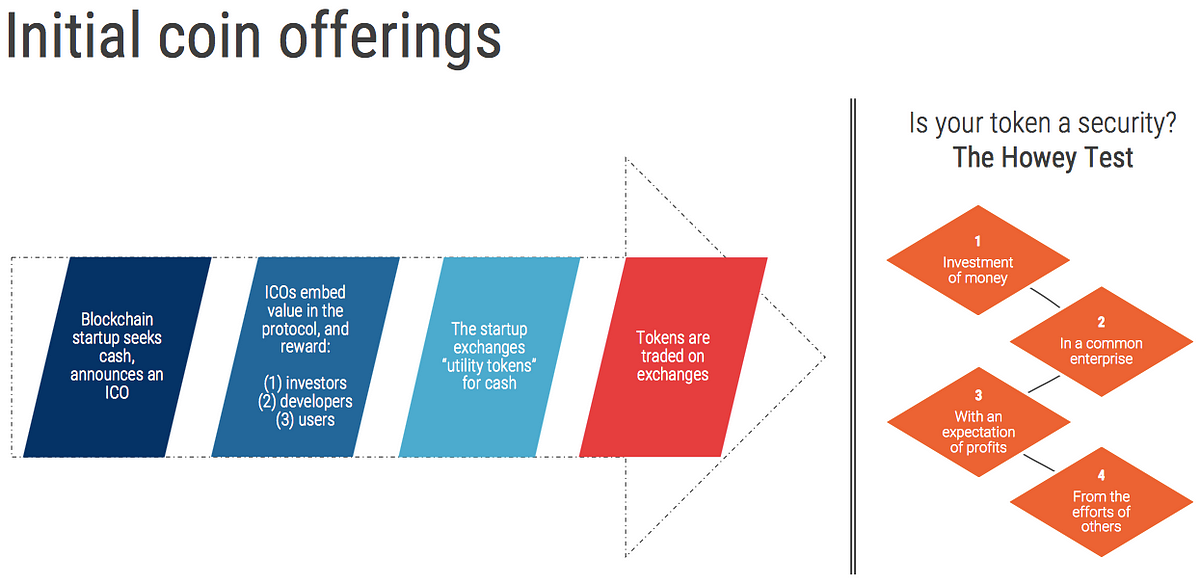

Securities regulations for ICOs

Currently, the US uses the Howey Test to determine what a security product is and has applied this to ICOs.Asked if she saw regulations moving to align with targeted regulations by the likes of Japan’s Financial Services Agency (FSA) as the sector matures, or aligning with the approach taken by the SEC that some construe as regressive, Goh notes: “The MAS has recently published “A Guide to Digital Token Offerings”, which indicates that a functional approach to regulatory classification of ICOs will be taken.”

“This is a common approach taken by regulators in the US and the UK. Currently, there are around 1000 cryptocurrencies in existence, with a wide range of functionality and uses. As such, regulators will need to be careful that the regulatory regime put in place for cryptocurrencies is adaptable enough to cater for their wide range of possible uses.”

“Given this is the case, and given the need to ensure that cryptocurrencies do not become a way of mimicking existing structures without out proper regulation, currently, the functional approach suggested by the MAS is a sensible way forward.”

And at a time when ICOs are being launched from jurisdictions such as the US, Switzerland, Singapore, Canada and the UK, Goh see’s a consensus regarding ICO regulations being eventually achieved on an international basis as the ICO market matures.

She observes: “ICOs are a global phenomenon, and one of their advantages is that they can be used as a mechanism to attract global investment. However, legal systems are designed on a national level, which means that there can be national, and sometimes even regional, variation as regards which rules apply to any given scenario.”

“One way to counter this would be to obtain international agreement on a set of standards which would apply to ICOs which would then apply globally. However, this can be hard to achieve in practice, as different regulators are still forming their view on how favourably to treat ICOs.”

“ Even if a broad agreement were reached, countries may well still differ on the practical detail of what has been agreed, for example, most regulators would agree that if an investor is wronged the investor should be compensation, but there is no universal concept of what “compensation” actually means.”

While the city-state of Singapore has no intention to regulate cryptocurrencies at this time, it already requires virtual-currency intermediaries such as exchange operators to comply with requirements to combat money laundering and terrorist financing. In addition, it is considering placing ICOs in a regulatory sandbox.

Singapore’s brand strength also lies in its reputation as a relatively clean city with firm rules and as an established financial centre, with the city-state’s government prosecuting businesses that misbehave. Dr Finian Tan of Vickers Ventures, one of the largest and oldest venture capital (VC) firms in Southeast Asia, has argued for the need of caveat emptor to prevail when it comes to ICOs.

Asked if regulations could see utility tokens being open to all investor categories but equity tokens restricted to accredited and professional investors as a way to balance the interests of investors and ICO issuers, Goh opines: “The concept of caveat emptor is a curious one as, even in Roman times, it was based on the fact that there was information symmetry between buyer and seller, and so each could independently assess the asset being sold.”

“However, in respect to ICOs, very few investors, even those who are fully accredited and professional, can say that they understand all aspects of how ICOs work. The genesis of caveat emptor, namely that the buyer can check the product being bought for himself, does not apply here, as the buyer is unable to fully check the product, but rather must rely on others to assert its validity.”

She concludes: “In fact, our experience is that many of those launching ICOs are, in fact, keen not to take too restrictive an approach towards regulatory and legal compliance, because of the ability to confirm that an ICO meets certain regulatory and legal standards gives that ICO legitimacy, certainty and, hopefully, greater value.”

“Therefore, we do not see a world in which security tokens will necessary never be open to retail investors, as firms may well be happy to meet retail standards to be able to sell to retail. Conversely, having a utility coin does not guarantee simplicity and security, and so it may well be that sales of these tokens are restricted to only some types of investors in some circumstances. The overall picture, therefore, may well not neatly fall within the security token/utility token divide.”