Banking the unbanked in emerging markets

by Joshua Bateman for TechCrunch

As countries progress, citizens migrate from remote villages to large cities and foreign countries. Their economic power rises and they participate in the global economy.

People need to purchase food, pay electricity bills, top up transportation cards, arrange online services, buy overseas goods, repay loans, and send money to relatives.

Unlike the U.S., however, where 93% of people have banking options, many in developing markets do not. Globally, an estimated 2 billion adults lack access to formal financial services. The services that are available are typically cumbersome and expensive.

To address this gap, fintech startups are offering online and mobile solutions, which consumers are welcoming. Younger generations are increasingly embracing online banking and almost nine in 10 people under the age of 30 live in emerging markets.

In 2011, Paul Wu founded GMobi, which created white-labeled app stores for mobile phone carriers. Subsequently, it launched a third-party mobile wallet. Roughly one-third of GMobi’s 100 employees now focus on the company’s worldwide mobile payments vertical, Reach Pay, its fastest growing revenue source.

Owing to cultural and language similarities, GMobi initially explored opportunities in mainland China. Powerhouses Alipay and Tencent Pay, however, already cornered the market. “We cannot go to China anymore,” Wu said, sitting in GMobi’s headquarters overlooking mountains on the outskirts of Taipei. “China is bloody competitive.”

Thus, GMobi turned to India where, after a couple years of preparation, they launched Oxymoney, a mobile wallet that facilitates data card top-ups and money transfers. Most users are in lower socio-economic demographics and don’t own PCs, which is why GMobi only offers mobile phone services.

After rural laborers move to New Delhi, for example, they can send money back to their parents. Today, customers often go to physical money transfer operations in cities, complete paper forms, and pay non-transparent fees. After a few days or a week, their parents receive the funds at a rural bank location.

Much of this hassle and inefficiency is eliminated through Oxymoney. In a boardroom, Wu explained the process while using an erasable marker to draw diagrams on a white board. The flow can be abbreviated as: (Consumer → Agency → Business → Consumer).

Using a mobile phone, the laborer sends money, which is routed through one of the country’s major money transfer agencies. Afterwards, because the consumer’s parents rarely have bank accounts themselves, the money is then sent to a shop in their village that does have a bank account. At the shop, parents pick up the cash.

The entire process takes about a day and the user pays a 1 percent processing fee. There’s no minimum, but GMobi’s 10 million Indian users typically send between USD $15-30 per transaction.

“We want to help the majority of the middle class, or even lower-middle class to increase their economic situation by improving the efficiency for these services,” Wu said. “We still need to educate the market because most of the workers, they still go offline. Still go to bank counters.”

Macro forces should propel usage. India, the world’s fastest-growing smartphone market, is forecast to have 1.4 billion mobile phone subscriptions by 2021. Additionally, Indian officials are pushing the G20 to reduce remittance fees and more remittances will be sent as India continues to urbanize, which constitutes one-third of the population currently.

With the Digital India initiative, the government of India is pushing the adoption of all things digital, including currencies and payments.

“We are growing very fast because that’s really helping,” Wu said.

Although the digital initiative can boost startups, critics exist. On his podcast, comedian Bill Burr opined on the control it provides third parties saying, “They’re on their way to micro-chipping all of us.”

Currently, GMobi only handles domestic money transfers. They are exploring cross-border solutions, but that brings additional cultural, operational, and regulatory complexities.

“In each country, you need the local license and you need the certain capital level and certain effort to connect to local banks,” Wu said. “So it’s not so easy to do cross-border.”

With anti-money laundering laws tightening, sending money between countries is a time-consuming process, often requiring the sender to do so in-person from a bank office. 100-employee dLocal, however, hopes to change that.

dLocal provides back-end infrastructure enabling merchants, mostly in developed markets, to accept payments from customers, mostly in emerging markets.

For example, when FaceBook, AirBnB, or Uber furnish services in Asia or Latin America, receiving payment is difficult owing to operational differences in each market. dLocal provides a single, integrated payment interface across more than 150 platforms such as SMS, mobile wallets, online transfers, credit cards, data cards, debit cards, and cash payouts.

dLocal chief executive and co-founder Sebastian Kanovich explained why the model succeeds. “Users in emerging markets do not have traditional international credit cards and they want to pay with alternative payment methods. And all vary across markets,” he said.

Nine years ago while living in South America, Kanovich saw demand. Consumers there ordered goods online, but rarely completed the transactions because they didn’t have internationally accepted credit cards. At that time, Kavonich did have an international credit card, which he routinely lent to friends.

“It was clear users had the intention to pay online, but the merchants were not ready to accept payments from them,” Kavonich said.

Owing to onerous know-your-customer (KYC) and anti-money laundering (AML) restrictions associated with retail channels, dLocal only provides commercial payment services. When speaking with central banks regarding P2P, “It becomes a whole different story. It becomes much more restricted,” Kanovich said.

In some markets, regulatory uncertainty poses challenges. “Rules of the game are not always 100 percent stable. Governments change and sometimes rules change,” Kanovich said. “That will be the biggest threat for us.”

Although there are hurdles, Kanovich is bullish. dLocal offers services in 18 countries today, but aims to be in almost 30 by year end. They are encountering strong growth in Turkey, Colombia, Argentina, Brazil, Peru, and Chile. Kanovich says Africa and Asia-Pacific, however, hold the greatest potential.

With dLocal, “Surfing the wave of globalization,” Kanovich said, “The opportunity is massive.”

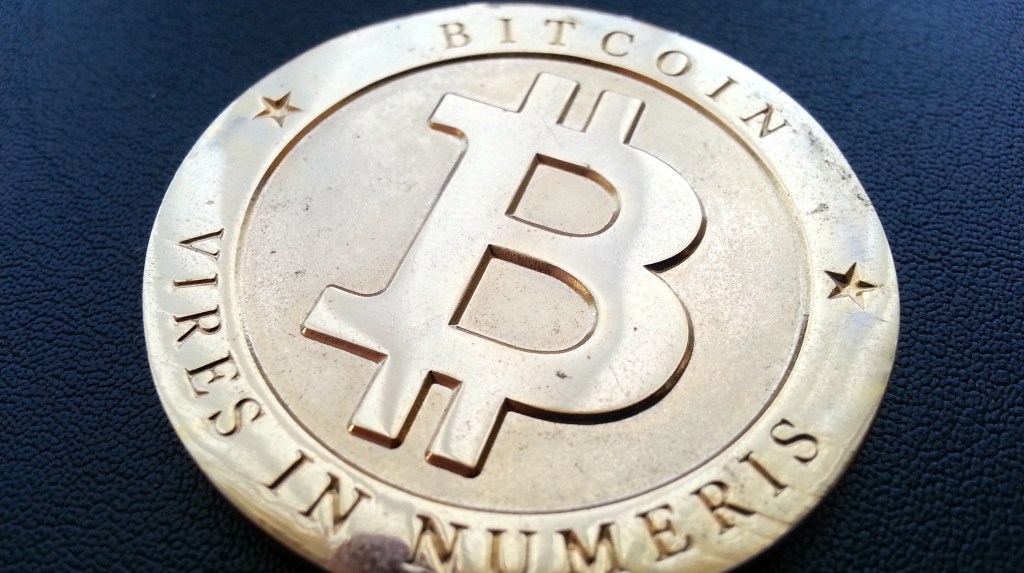

Another source of potential growth is to incorporate digital currencies, which dLocal does not do today. Kanovich personally advocates for Bitcoin, but says banks in emerging markets are weary. “We just need to wait for it to become slightly more mainstream before we can convince central banks everywhere that it’s okay,” Kanovich said.

Philippines-based Coins, which recently announced a funding round, is embracing digital currencies. The company facilitates bill payments, money transfers, buying phone credits, and online purchases globally.

Coins was founded “To bridge the gap in financial services,” according to Justin Leow, head of business operations. “There’s a huge disparity in access to financial services, especially in developing countries.”

One market segment they serve is P2P cross-border remittances. If a laborer or domestic helper moves to a foreign country, Coins assists them in sending remittances more cheaply, efficiently, and quickly than conventional channels like money transfer operators. Traditional channel fees can reach 10%, Coins is in the 2-3% range.

Take, for example, a domestic helper in Hong Kong earning USD $700 per month and sending half, $350, home to the Philippines. Reducing the fee from $35.00 (10%) to $10.50 (3%) is meaningful.

Globally, an estimated $601 billion is remitted annually, and developing countries garner almost three-fourths. In the Philippines alone, where 10% of its citizens live outside the country, $28 billion is remitted across borders annually, according to The World Bank data. Remittances to the two largest recipient countries, India and China, exceed $60 billion.

Banks often require high minimum balances, which is why fewer than one-third of Filipinos have accounts. There are more Facebook users in the country than bank account holders.

“So there’s a huge segment of the population banks aren’t able to tap, but we think that we can because of the model we’ve taken.” Leow said.

Coins uses digital currencies such as Bitcoin and Stellar. “That’s the only reason why it works as a medium for doing remittances around the world,” Leow said.

Although using complex block chain technology, Leow said customers don’t need to fully comprehend the behind-the-scenes processes. “All they’re concerned about is disbursing the payment on the other end.”

Digital currency adoption does not, however, imply doom for banks. “We require [banks] to run. And in exchange we also are able to drive more usage to their services, reaching a demographic that they’ve been unable to reach on their own,” Leow said.

This benefits consumers. Traditional banks often know little about their customers, but technology companies can easily record data on their preferences and habits in order to better tailor solutions to customer’s needs.

For the companies serving the unbanked, there are both financial and social benefits.

“It’s a very exciting opportunity and we can also make a huge impact on the lives of lots of people,” Leow said.