Singapore fintech: Digital wholesale banking arrives

Euromoney magazine

In June, Singapore’s regulator will hand licences to three new wholesale digital banks in a bid to better serve under-banked SMEs. Euromoney talks to Arival Bank, a fintech firm aiming to snag a licence and use it to fuel its global ambitions.

And so to the next stage of digital financial disruption. Last summer, the Monetary Authority of Singapore (MAS) said it would accept bids for five new virtual banking licences, with the winners to be announced around June 2020.

The MAS says it received 21 tenders and that the bids break down into two types. At least five bids have been lodged for full-service digital banks, to be whittled down to two by mid-year. Licensees have to stump up S$1.5 billion ($1.08 billion) in paid-up capital, must be based in Singapore and ultimately controlled by a local business interest.

Then there are the licences for new digital wholesale banks, coveted by at least nine companies and consortia. This is new and a further sign that disruption is moving beyond retail to the nuts and bolts of wholesale banking.

The applicants include some of the biggest names in fintech and in technology in general. Among those bidding for a wholesale licence are Chinese firms Ant Financial and TikTok, and Singaporean internet operators Sea and Razer. Several are consortia, bringing together Hong Kong financial group AMTD with Chinese smartphone maker Xiaomi, and telecoms operator Singtel with delivery firm Grab.

Some are firms few will know outside the world of fintech. Take Arival, founded in 2017 in Singapore with a stated mission to “bring a new level of banking service” to small and medium-sized enterprises.

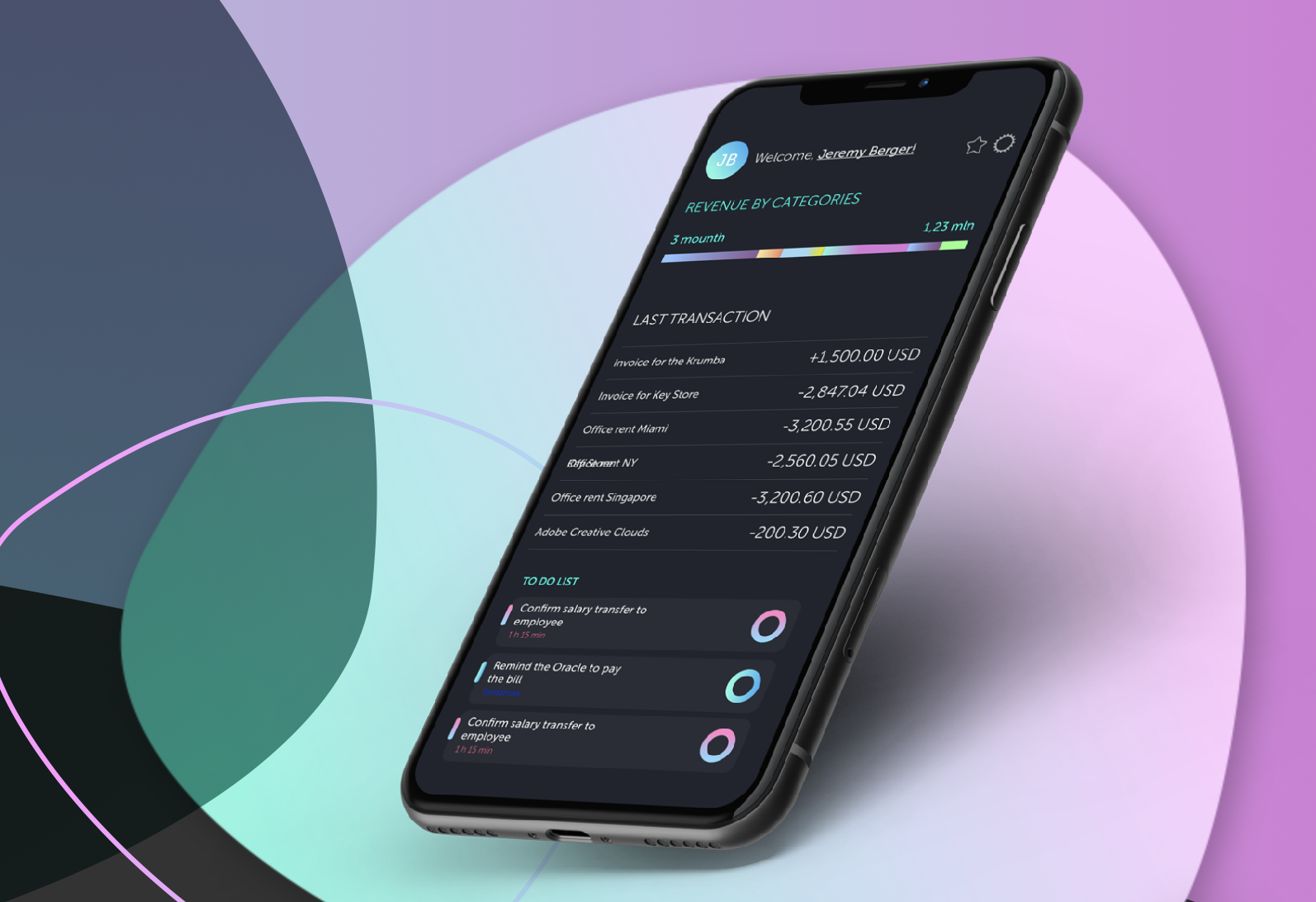

Our initial customer focus is tech startups. That is the world where we most resonate. Within two years, we will be a leading financial provider for these firms, their go-to digital bank

Jeremy Berger, Arival

When Euromoney meets its co-founder and COO Jeremy Berger, he is in Miami overseeing a Puerto Rico-based team in the final throes of applying for a US digital bank licence.

Berger spends a lot of time in the air. Arival is also applying for a full digital banking licence in Lithuania, where Berger’s team is about to open an office in the capital Vilnius.

Other markets on the firm’s radar are Malaysia, the UK, Australia and the UAE, with Hong Kong and Taiwan also on its wish list. But it is Singapore that interests the young firm most.

Berger met his business partners, chief executive Vladislav Solodkiy and president Igor Pesin, both Russian nationals, at Money 20/20, an annual conference in Las Vegas about the future of payments and fintech.

Solodkiy, who cut his teeth in media and marketing at two of Russia’s largest lenders, Russian Standard Bank and Alfa Bank, before jumping into fintech, launched Arival in October 2017. Pesin and Berger joined a few months later.

Solodkiy’s CV is surely a sign of things to come as banking becomes more seamless and online. The leading providers of the future, Berger reckons, will be a melting pot of “industry experts, designers, artists, marketing gurus and young entrepreneurs”.

He says that as a rule, virtual lenders “prefer to hire young, hungry and driven individuals with a clear mind and the willingness to learn, adapt and innovate” rather than employing “old bankers”.

‘Startup paradise’

Singapore was the obvious place to locate Arival’s global operations, Berger says, pointing to its global outlook and willingness to welcome outsiders.

“It’s a startup paradise, with a lot of foreign-run fintechs, a supportive ecosystem and real fintech talent,” he says. “It’s full of ambitious digital firms looking for innovative digital financial services.”

The firm spent its early days helping corporates and mainstream lenders tackle compliance issues, including money laundering, and little else. But given its history – Arival sprung out of a $40 million venture capital firm called Life.Sreda, whose early fintech deals include a profitable investment in Russian neo-lender Rocketbank – its ambitions were always set on becoming a transnational digital bank.

Then came last year’s announcement by the MAS.

Singapore at the state level is a cautious operator, focused on pursuing accretive gains while keeping an eye on the bigger, long-term picture. The new wholesale licences fit into this framework. It involves risk, but it is contained.

Innovation is the aim, but it is kept caged until it is fully trusted. Successful applicants will be allowed to serve SMEs and other non-retail segments, and can only take fixed deposits of over S$250,000 from individuals.

Each licensee must have to hand minimum paid-up capital of S$100 million and will be restricted at first to just one physical place of business. After the winners are announced, there will be a period of bedding-in, before operations start in earnest from mid 2021. If the regulator likes what it sees, the new banks will be allowed progressively to expand their capital base, up to a limit of S$1.5 billion, and their service offering.

Berger wants Arival to be “a real borderless fintech bank for rejected businesses and entrepreneurs”, eventually with operations around the world.

While the application process in Singapore is still at a “very nascent” stage, he is “confident that we will be one of the finalists”.

Should it win, the firm will target its product offering at fintechs and the wider digital community, including bloggers, streamers and influencers, but also charities and freelancers.

“Our initial customer focus is tech startups,” Berger says. “That is the world where we most resonate.”

Higher-risk customers are the reason why we go to bed thinking about compliance and wake up to the very same thought

Jeremy Berger

Based on an internal digital analysis of 2,000 customers, Arival identified 12 products to integrate into its platform, including business bank accounts (delivered via its own banking platform, ArivalOS), international payment transfers, foreign exchange, business expense and debit cards, factoring, and financial management services, including analytics and accounting.

“Within two years, we will be a leading financial provider for these firms, their go-to digital bank,” Berger says.

He is keen to stress that Arival will be “the first fintech bank for SMEs. We’re not a neobank or challenger bank.”

He says neobanks that align with traditional lenders are too restricted in their ability to serve the under-banked, while challenger banks such as N26 and Revolut are often seen as back-up banks rather than primary providers.

Arival’s “full range of products and services” and open infrastructure will, he hopes, result in customers ditching their traditional provider and hopping on board.

He is careful not to rock the boat too much, however, balancing the firm’s ambitions with a nod to Singapore’s need to create growth and guarantee social cohesion. That means focusing on job creation and on innovation, but not at the expense of allowing margins and good ideas to be crushed by over-competition.

To that end, he says: “I don’t think we will disrupt the local market. It’s dominated by three or four banks and that’s not going to change anytime soon. But more fintechs will spring up here or come to Singapore, and that development coexists nicely with our wider strategy.”

Insiders reckon the bidding battle for a full digital licence will come down to which firms are better known and more reputable, implicitly trusted by government and bolted firmly to the economy.

That should put the Singtel-Grab consortium in prime position. Many see it as a shoo-in for one of the full licences, although Eugene Tarzimanov, Asia senior credit officer at Moody’s financial institutions group, points to the threat of a telecommunications firm “entering the retail banking space and actively cross-selling banking products to its already vast client base, by adding perks such as free Wi-Fi. If they get the right partner who knows how to do banking and credit, they will certainly pose a competitive threat.”

On the wholesale side, the ball is still up in the air.

Dennis Khoo, TMRW Digital Dennis Khoo, regional head at TMRW Digital Group, Singapore lender UOB’s first fully digital bank, says: “The questions the regulator will ask are: ‘First, what are you bringing to the table that your rivals aren’t; and second, are you raising productivity?’ That’s a key question given Singapore’s incremental gains-based growth model.”

In terms of paid-up capital, the MAS has set the bar at a reasonable height for applicants. It’s a decent chunk of money. But as Khoo notes sagely: “Banking isn’t necessarily something you can ‘try’.”

He believes the big opportunity for new digital wholesale banks will be in disbursing credit to underserved or unbanked SMEs. But he adds that a new entrant “must have a different way to underwrite. New digital wholesale players will likely focus on the credit business and then expand into FX and remittances.

“Data will be key in the credit business. If you can find better, quicker and more seamless ways to underwrite, you’re always going to have an advantage. And there, good data and interpreting that data will be important.”

USP

Arival clearly marked out several of those questions in advance. Berger says the firm will “seek to bundle fintechs together. The regulator wants to encourage more fintechs to work together on one banking platform. That’s where we come in.”

Where the firm can offer a unique selling proposition in the eyes of the regulator is its expertise in compliance and background checks. This is no small thing. Arival’s A.ID platform is described by Berger as “cutting-edge compliance”, a “differentiator” that performs know-your-customer checks, tackles money laundering and meets compliance needs.

Most banks, he says, view compliance as “an obligation, a headache and an expense. It isn’t their passion or key feature, or a channel to generating money for their founders and shareholders. Compliance is our ‘secret sauce’.”

You can call that good marketing or good anticipation, a sign of a company working to its strengths. Arival was aware from the start that the regulator’s chief concerns would revolve around compliance.

“We wanted to be able to answer questions around how we check our clients and on-board them, and why our bank won’t be used for money laundering or other criminal activities,” says Berger.

Compliance, he says, is “really what keeps the regulators’ blood flowing. Higher-risk customers are the reason why we go to bed thinking about compliance and wake up to the very same thought”.

The regulator will be heartened by those words. If there is a concern over the new digital wholesale banking applicants, beyond an ability to stay the course, it is the threat presented by the darker side of the digital world.

Hackers working for bad actors like to prod and poke at new digital platforms, locate any soft spots and use them to launder and pilfer for profit.

Disruption in retail banking is established, a fact and a way of life. There is no turning back the clock. This summer in Singapore, a new chapter in this story will start, as three new financial providers are handed the right to offer digital wholesale products to underserved corporates in the Lion City.

After that, it’s up to the disruptors to prove they are worthy of the customer’s and the regulator’s trust.