How Much Should You Raise in Your VC Round? And What is a VC Looking at in Your Model?

By Mark Suster from UpFront Ventures for his blog

There’s a quick litmus-test conversation any early-stage VC will have with the founder and it’s one that you should be as prepared for as your elevator pitch. It goes something like this …

VC: “How much money are you raising?”

Founder: “$8–10 million”

VC: “What’s your current burn rate?”

Founder: “$250k / month.”

VC: “So at a constant rate of burn rate you’d be raising enough for 2.5–3 years. Why are you raising so much?”

Founder: “Um. Let me check my plan.”

Usually that’s the point in the meeting where a VC realizes that this meeting isn’t going to go very well.

There are many things a VC is looking for in reviewing your business plan but beyond things the like the quality of revenue, margins, OPEX and CAPEX there’s a really simple rule I call, “Cash In, Cash Out, Milestones Achieved.”

Simply put, a VC wants to evaluate how much cash you’re raising and whether this amount is realistic. He or she wants to know how long the money you will raise will last and whether this is long enough to warrant taking a risk on funding you. Finally, the VC wants to know what your progress will look like at the end of this period to know how easy it will be for you to raise your next round.

If you don’t have a firm grasp of these concepts and how a VC thinks your meeting is dead.

Cash In

Cash in. It’s the amount of money you’re raising. A VC is looking for reasonableness. Are you raising an appropriate amount of capital relative to your progress, relative to your team size and relative to your needs?

Of course the VC is looking to have specificity in how you plan to spend the money you’re going to raise and plans that show a pie chart that says, “25% on marketing, 30% on technology and R&D, 20% on infrastructure, 25% on G&A” do not get funded. Yes, I see plans this pedestrian.

VCs want you to raise the “appropriate” amount of capital, which I would define as what is reasonable given your progress to date, your resources and your needs for an 18–24 month period. VCs tend not to want to fund founders who raise too much money in a given round also because they know that sometimes having too many resources will lead to founders burning through cash too quickly. Conversely many VCs believe that constraining cash can often lead to increases in creative solutions at a startup.

One entrepreneur refrain I sometimes hear is “We want to raise some extra money for M&A activities.” This is a red flag for VCs. A VC wants to know that you have a solid plan to execute a stand-alone business and if you require capital for an acquisition they’d rather evaluate it at the time rather than over-fund you now. It’s true that some later-stage private equity firms like to fund “roll ups” (a company that acquires many related companies in it sector), but this is seldom the domain of VCs.

Every VC knows that the amount you raise is often a proxy for your valuation. VCs in early stage round assume that you will likely take 20–25% dilution for your funding round so if you’re raising $8–10 million they will assume your expectation is $24 million pre at the low-end of the range ($8m x 4 = $32m post money with $8m capital injected buying 25% of the company) and $40 million pre at the high end ($10m x 5= $50m post money with $10m capital injected buying 20% or $40m pre).

So when you say $8–10m is your goal and you aren’t at all thinking about your valuation know that a VC hears “$24–40 million pre-money valuation expectations.” Of course there are times where 15% dilution is more appropriate and other times it can be 33% but in a first meeting we’re just trying to establish general ranges for reasonableness.

If you’ve only ever raised $500k, have limited revenue, have 7 people at your company and aren’t a serial entrepreneur it’s a pretty tall order to imagine going straight to $8–10 million unless your data is very compelling or you’ve otherwise become “hot.” If you’ve raised $3 million previously, have $250k in monthly recurring revenue and 23 staff an $8–10 million round might be more down the fairway.

One big mistake I see many founders make is asking for an unrealistic amount of money in the fund raise. VCs will quickly qualify themselves out in what might have otherwise been a chance for you to get them to engage in a process. I always advise people to ask for slightly less than they need because if your ask is reasonable and you get multiple firms interested then it’s easy to increase round size and valuation later in the process. Every VC wants to fund a deal that seems to have too much demand. Having too little demand leads to bankruptcy.

A VC won’t necessarily tell you that they find your months of cash unrealistic, your plans not well formed or your valuation out of range — they’re more often likely to tell you, “It’s not a great fit for us at the moment. We’d love to see you again when you have a little bit more traction.” That’s what’s called a “soft no.”

Annoying, I know. But that’s the reality. So it’s incumbent on you to know what a smart business plan and use of cash looks like.

Cash Out

Cash out is when you’re out of money. In general it is expected that you’ll be raising 18–24 month’s of cash in a VC fund raising. If you have a shorter runway than that the time you’ll have to make enough progress to raise more capital is too short. Assume that you’ll need to be raising for 3–6 months prior to closing your next round so the last thing an experienced VC wants is you on the fund-raising trail in 6–9 months. Having a minimum of 18 months runway means you have 12–15 months to make progress before the market will weigh in on your progress.

On the other side, VCs often don’t want to see a plan that funds longer than 2 years and seldom do they want to see 3 years. Sometimes I hear entrepreneurs make claims like, “I’m raising extra cash as a cushion” but this usually falls on deaf ears with a VC. They don’t want you experimenting for many years on their capital — they’d rather you come back to market in 2 years and they can see what you’ve accomplished before deciding whether to give you more money. You might not like this — but if you know it’s how most VCs think it you will be better prepared for your conversations.

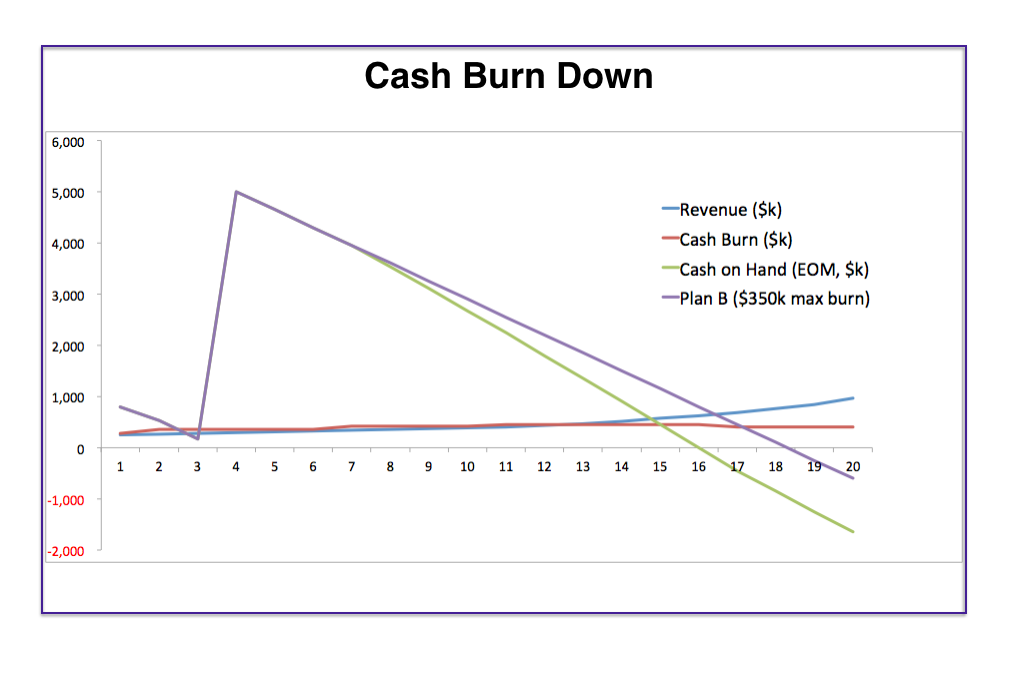

At the top of the post I’ve attached a simple example graphic of a cash burn down chart that any VC will want to see in spreadsheet or visual form and doing it on your own will help you internally with scenario planning well before you’re even fund raising.

In the example I’ve provided I assume you’re raising $5 million by month 4 of your plan. In the normal case you’d be running out of cash after 16 months or just one year after you raise money. I built a “plan b,” which in this case just holds burn rate constant at $350k and has you out of cash in month 19, which gives you more runway. In reality this fund-raising plan should take you to month 22, which would be 18 months since you’ve raised.

[Note: If you enjoy or are learning from this series please subscribe by entering your email below — it saves me from having to spam you too much on Twitter :)]

Milestones Achieved

Assuming a VC has shown interest in your team, your plans, your market and they believe that you’re raising an appropriate amount of capital, sooner or later they’ll begin thinking about the milestones you would have achieved by the time you’re raising your next round of capital or by the time you’re out of money.

Most VCs lead one round of financing in your company and are looking for other VCs to lead subsequent rounds. Knowing that it’s more likely that an outsider will fund your next round a VC will be thinking the following:

- What will you have accomplished by the next time you go out to raise?

- Will this be enough for another VC to show interest?

- Will these milestones be enough that a VC would pay a higher price in the next round of financing?

- If you’re not able to raise from outsiders and I need to lead this round, will you have made enough progress for me to face my partnership and tell them why we should fund an inside round? Will your burn rate be sufficiently low that I won’t worry about the amount of capital you’ll need in the next round of financing?

VCs want to fund innovations but they are also very cognizant of how much firm risk they can take on given the size of their fund and the number of deals they want to do per fund.

Summary

Raising money is a daunting process. This part of a series to help you raise venture capital — the first post is in that previous link along with the whole outline.

If you know the financial factors that a VC is evaluating: cash in, cash out & milestones, you’ll have a much easier time in your VC meetings. In the next post I’ll give some advice on how to talk about valuation when a VC asks.

Happy raising.