Coinbase: The Heart of the Bitcoin Frenzy

By Nathaniel Popper for The New York Times

By Nathaniel Popper for The New York Times

The San Francisco start-up has been at the center of the virtual currency boom. But like any young company, it is experiencing growing pains.

The booming stock market of the 1920s had the New York Stock Exchange. The tech bubble of the 1990s had Nasdaq and E-Trade. And the virtual currency market of the last year has had Coinbase.

Coinbase has been at the center of the speculative frenzy driving up the value of bitcoin — which topped $13,000 Wednesday — and similar currencies. While there are many bitcoin exchanges around the world, Coinbase has been the dominant place that ordinary Americans go to buy and sell virtual currency. No company had made it simpler to sign up, link a bank account or debit card, and begin buying bitcoin.

The number of people with Coinbase accounts has gone from 5.5 million in January to 13.3 million at the end of November, according to data from the Altana Digital Currency Fund. In late November, Coinbase was sometimes getting 100,000 new customers a day — leaving the company with more customers than Charles Schwab and E-Trade.

The company faces challenges that are a reminder of the early days of now-mainstream online brokerages, which suffered through untimely outages and harsh criticism from traditional finance companies and government regulators. And Coinbase’s missteps make it clear that the virtual currency industry is still young, with little of the battle testing that other financial markets have faced.

Coinbase’s offices in downtown San Francisco show a startup straining to keep up with growth. The company offers all the usual perks: free lunch and dinner, a sizable cafeteria and a room with yoga mats and board games.

Recently, every last inch of space has been pressed into action. The day after bitcoin hit $10,000 last week, a training session for Coinbase managers was moved to the game room because the engineering team needed to set up an emergency war room in the regular conference room.

The engineering team was trying to get Coinbase back up after the company’s site was knocked offline, overwhelmed by a wave of incoming traffic. The number of visitors was double what it had been during the previous peak — two days earlier — and eight times what it had been in June, the peak until recently.

All the big bitcoin exchanges went down for at least part of the day, and Coinbase got back online faster than most. Still, any sort of downtime like that would be unacceptable in more traditional exchanges where stocks and commodities are traded.

“There are some well-known places this year when we weren’t able to keep up with the volume,” said Jeremy Henrickson, the chief product officer at Coinbase. “We are not where we need to be yet.”

Most Friday afternoons, Brian Armstrong, the chief executive of Coinbase, holds a session in the cafeteria where employees can ask him anything. On the Friday of the record-hitting week, Armstrong discussed how the company was planning to grow and introduced Asiff Hirji, the new president and chief operating officer who will help him oversee it all.

The addition of Hirji, who had the same role at TD Ameritrade, was an implicit recognition that this new industry needs more seasoned hands to help young executives like Armstrong, 34. Hirji will manage Coinbase’s trading operations while Armstrong focuses on new projects.

Armstrong has been running Coinbase since he co-founded it in 2012. Soft-spoken and reserved, he is an unusual figure in an industry filled with loud ideologues. He has done few public appearances during bitcoin’s recent bull market, and he recognizes the current frenzy has come with downsides.

“It’s probably a little bit too focused on the price or people trying to make money,” Armstrong said last week. “The thing I’m passionate about with digital currency is the world having an open financial system.”

There is some irony to the success Armstrong has experienced as a result of bitcoin’s rising price. In 2015, he helped lead a push to get the bitcoin network to expand so it could handle more transactions. That effort failed, and Armstrong said in a recent interview that bitcoin “did break my heart a little bit.” He said he now holds more of his wealth in a bitcoin competitor, Ether, which Coinbase also offers to customers.

Most of the screens in the Coinbase offices show the performance of the company’s servers and customer metrics — like the number of customers downloading its iPhone app. For a time last week, Coinbase was among the 10 most downloaded iPhone apps, ahead of Uber and Twitter.

There are a few screens, including one in the cafeteria, that show the price of bitcoin, Litecoin and Ether, the three virtual currencies that Coinbase buys, sells and holds for customers. Litecoin was created by a former Coinbase employee and is often described as silver to bitcoin’s gold. The newer Ether, which lives on the Ethereum network, is the second most valuable virtual currency after bitcoin.

Coinbase set itself apart from other early bitcoin companies when it was one of the first to get a new, special license for virtual currency companies in New York, called the BitLicense.

In the last year, though, Coinbase’s most notable interaction with the government came after the IRS asked the company to hand over all of its customer records. Bitcoin holders are supposed to pay taxes if they collect gains from selling coins, but the IRS has said that only a few hundred people have done so each year.

Coinbase fought the broad request from the IRS and last week, while the price was skyrocketing, announced an agreement to hand over only the records of customers who made transactions involving more than $20,000 of virtual currencies — around 3 percent of the company’s customers.

In addition to the brokerage service for small investors, Coinbase also runs an exchange, called GDAX, tailored to larger investors.

GDAX is overseen by Adam White, a former Air Force officer and a graduate of Harvard Business School. The day bitcoin hit $10,000, he was in New York speaking with big financial institutions that are looking into bitcoin. Some companies are getting ready to begin trading bitcoin futures contracts this month, when that activity becomes available on the Chicago Mercantile Exchange.

A year ago, his Wall Street outreach was difficult, but “it’s all inbound now,” White said.

Not surprisingly, Coinbase is on a building spree. It recently leased office space in New York that will handle the Wall Street business and a new service that holds virtual currencies for large customers. In San Francisco, the company is adding two new floors in the building where it now has one.

Still, the main concern among virtual currency investors is that Coinbase has not expanded fast enough. In May, the company was criticized by a customer who could not reach anyone at the company after his account was hacked.

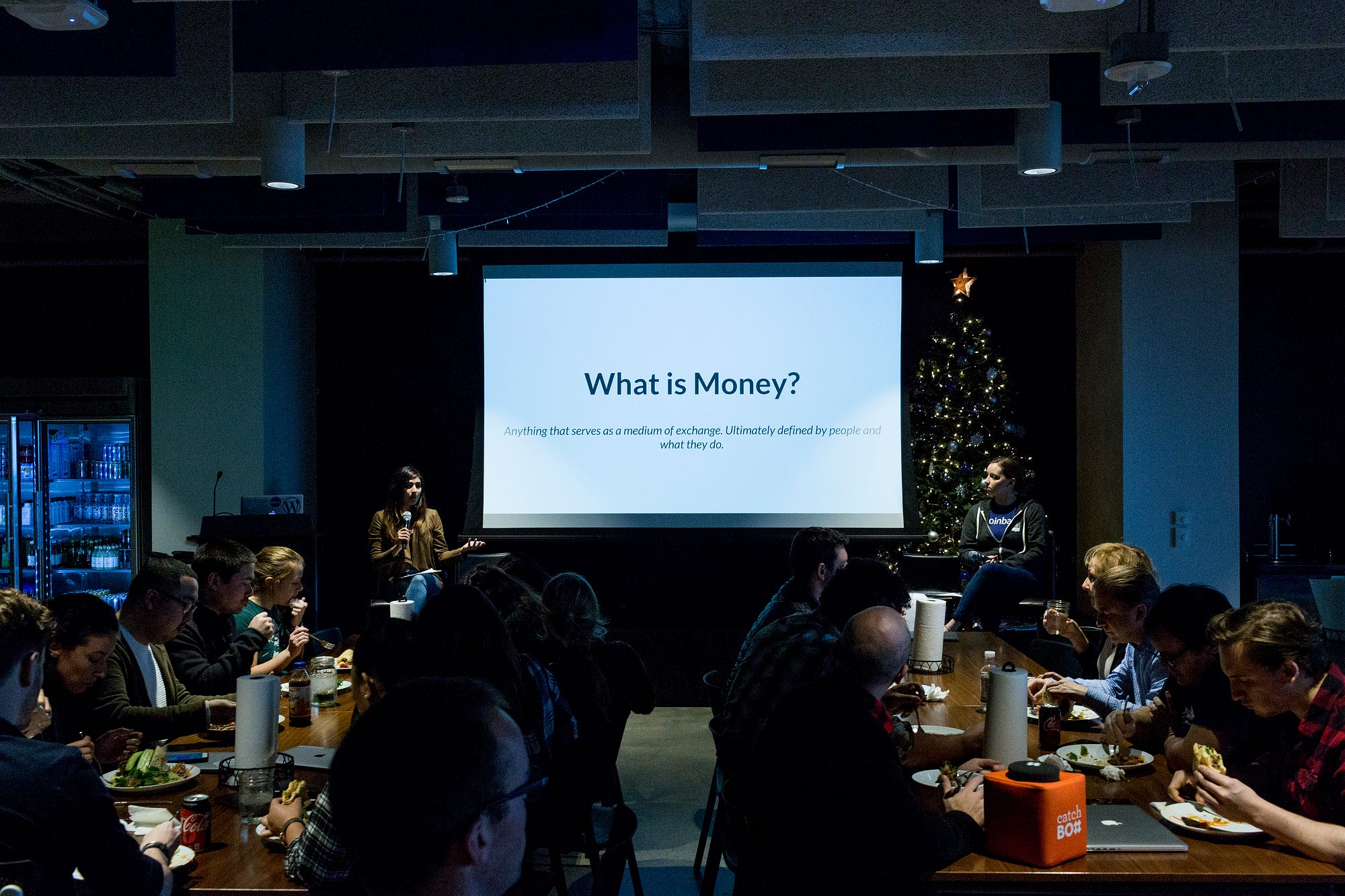

Coinbase is trying to be more responsive. At the beginning of the year, the company had 24 employees providing customer support. It now has around 180, with most of them outsourced from a call center in Texas and an email response team in the Philippines. The cafeteria is often turned into a “Crypto Club” where new employees are taught the ins and outs of virtual currency.

Daniel Romero, the general manager of Coinbase, said he wanted to have 400 customer support employees by the first quarter of next year to provide phone support around the clock. But in the meantime, there is a 10-day backlog of service requests.

“When your customer support issues are that publicly bad, and you have your site go down when people want to be trading,” it’s a very humbling experience, Romero said.

For more great stories, subscribe to The New York Times.