The other big risk in auto lending

By John Reosti for American Banker,

GrandSouth Bancorp’s woes could be warning sign for banks that lend to auto dealers.

The Greenville, S.C., company eked out a first-quarter profit as losses spiked in its national automobile floor plan lending business. The business, marketed as CarBucks, provides credit to dealers so they can buy used cars and trucks to sell to consumers.

A decline in wholesale prices at the end of 2016, combined with a delay in federal tax refunds, slowed auto sales and spurred a number of delinquencies and chargeoffs among dealers, said J.B. Schwiers, the $560 million-asset company’s president and CEO. Nearly 90% of the quarter’s $1.8 million in chargeoffs were tied to floor plan loans.

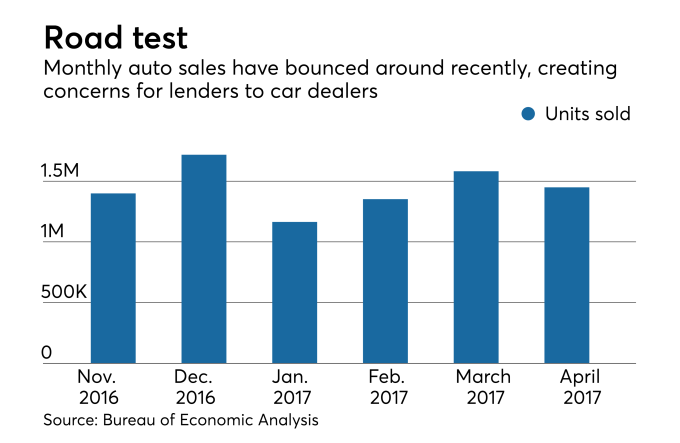

GrandSouth’s challenges, combined with a stagnant auto market, could draw more attention to floor plan lending, where dealers pay down their balances as inventory sells out. Auto sales were down 3.4% in April from a year earlier, with 17.2 million units sold, according to data from the Bureau of Economic Analysis.

“We knew we had an issue in February,” Schwiers said, though he added that conditions normalized in April.

To be sure, vehicle sales increased in April, ending three straight months of declines. Still, another downturn could cause new challenges, especially for banks that deal with clients outside their local markets.

Jack Hartings heads the $465 million-asset Peoples Bank in Coldwater, Ohio, which has been making floor plan loans to local clients for three decades.

The business requires “very hands-on financing,” said Hartings, Peoples’ president and CEO. “You need to be able to go out there and do floor plan checks once a month. … I think you start losing that when you get a little distance between your office and where those dealers are at. To be successful, I think you need to be more boots-on-the-ground close.”

Another distinction can be drawn based on the level of competition and the types of vehicles being sold.

GrandSouth’s national platform puts it in competition with heavyweights such as Wells Fargo, Bank of America and BB&T. Such competition can put pressure on rates and terms.

At the same time, GrandSouth predominantly lends to independent used-car dealers, which can present challenges when it comes to the underlying value of the vehicles sold. Valuations can fluctuate wildly depending on demand.

“When car sales slow rapidly the wholesale price just drops to the floor,” Hartings said. “That vehicle that maybe somebody paid $10,000 or $15,000 for is now worth $6,000 to $8,000. … The wholesale market drives risk more than the retail market.”

Floor plan loans made up roughly a fifth of GrandSouth’s loans at Dec 31. In comparison, less than 5% of Peoples’ portfolio involves floor plan loans.

Such scale — GrandSouth has more than 1,000 dealer clients in more than 22 states — helped supersize profits in good times, but it also presents challenges when conditions soften. The company earned $17.1 million from 2013 to 2016. In the first quarter, profit totaled $65,000.

Despite the disappointing start to 2017, GrandSouth has no plans of scaling back even though losses will likely top historical norms through the rest of this year.

“Pulling out would be a very tough thing to get over reputation-wise,” Schwiers said. “Floor plan lending has been good to us over the years. We want to continue.”

Schwiers, who became CEO in October, wants to diversify.

For instance, GrandSouth has gotten into agricultural lending. Since entering the business last year, it has built a $4 million portfolio, an amount it hopes to triple by the end of this year.

The company has also expanded geographically, hiring two former Synovus Financial bankers in May to oversee an expansion into Charleston, S.C. Rob Phillips was president for the coastal region of Synovus’ NBSC division, while Alan Urum managed the Charleston operation.

Charleston’s population has grown by 20% since 2010, to 149,000 residents, and several big corporations, including Boeing, Mercedes-Benz and Volvo, have opened production facilities.

Wells Fargo and Bank of America control about 40% of the city’s deposits, based on June 2016 data from the Federal Deposit Insurance Corp.

Charleston is also luring a number of growth-minded banks.

United Community Banks in Blairsville, Ga., made a push into the city last year when it bought Tidelands Bancshares. Pinnacle Financial Partners in Nashville, Tenn., will gain nearly 5% deposit market share when it buys BNC Bancorp, a High Point, N.C., company that had been expanding in the area.

For GrandSouth, the move allows it to have operations across its home state.

Charleston “gives us a presence in all the major markets” in South Carolina, Schwiers said. “I’m pretty excited about the potential of us being there. … The area is exploding.”