Wealth of people in their 30s has ‘halved in a decade’

By BBC

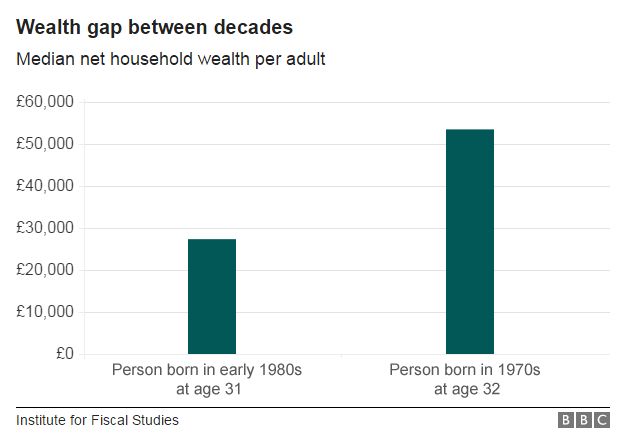

People in their early 30s are half as wealthy as those now in their 40s were at the same age, a report finds.

Today’s 30-something generation has missed out on house price increases and better pensions, according to research by the Institute for Fiscal Studies.

Those born in the early 1980s have an average wealth of £27,000 each, against the £53,000 those born in the 1970s had by the same age, said the IFS.

They will also find it harder to amass wealth in the future, it added.

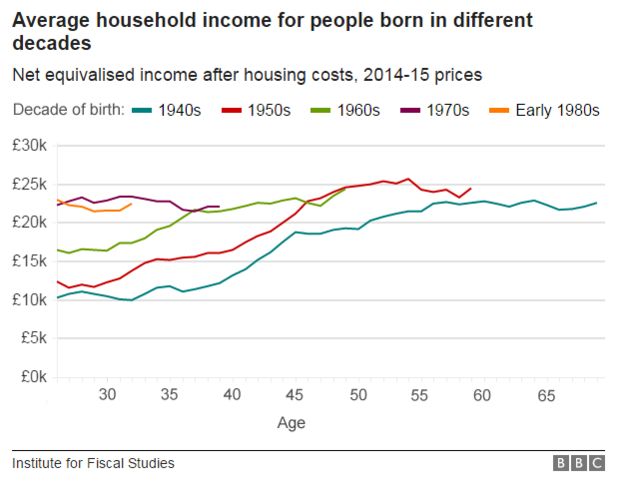

The think tank found that people born in the early 1980s were the first post-war group not to have higher incomes in early adulthood than those born in the preceding decade.

“This is partly the result of the overall stagnation of working-age incomes,” it said. “But it also reflects the fact that the great recession hit the pay and employment of young adults the hardest.”

‘It’s a vicious cycle’

Jessica Lucas, 27

A lot of my friends can’t find a way to get a deposit for a house. A lot of them are struggling – working full time, sometimes working two jobs – and that’s just to rent.

Renting alone is causing us a lot of trouble to save up for a house, so I don’t know how we’re going to get out of the vicious cycle of renting to then own.

Adam Snape, 36

For pretty much everyone I know around my age it’s hard to get a house. Everyone was spending on credit cards that were limitless and people could get another one and another one.

People didn’t think they needed a plan really.

What is the norm now is renting. It’s getting a lot more like Europe. It’s becoming a bit of a daydream that people can buy a house.

Private Pensions

“It looks like those born in the early 1980s are likely to find it harder than their predecessors to build up wealth in housing and pensions as they age,” said report author Andrew Hood.

“They have much lower home-ownership rates in early adulthood than any other post-war cohort, and – outside the public sector – have much less access to generous defined benefit pension schemes than previous generations did at the same age.”

“Wealth” as defined by the IFS includes property, savings and investments, and money held in private pensions – minus any debts a person may have such as student loans or credit cards.

Analysis

By Simon Gompertz, personal finance correspondent

There is plenty to celebrate for younger generations: better health, longer lives, more interesting food, travel and technology.

But there is no avoiding the financial hit which thirty-somethings have suffered as latecomers to the property and pensions game.

It’s as if they had sat down to a Monopoly binge on a rainy afternoon, only to be told they couldn’t collect £200 on passing go and couldn’t have any houses of their own.

They could only rent.

What does the future hold if you are in your early 30s?

There is little sign of the situation getting any better. Property prices remain out of reach for many. Few have the gold-plated pensions of yesteryear.

The worst case scenario is the thought of millions reaching old age, still renting, with paltry savings and more likely to turn to the state for support.

Campbell Robb, housing charity Shelter’s chief executive, said: “With sky-high house prices so out of step with average wages, it’s no wonder a whole generation are being priced out of a home of their own and left with no choice but expensive, unstable private renting.

“At Shelter we see the impact of our chronic shortage of affordable homes every day, with thousands of people forking out most of their income on rent and left living from one pay cheque to the next.”

Laura Gardiner, from the Resolution Foundation think tank which works to improve the living standards of those in the UK, said this was not just a problem for the 30-something generation – often referred to as Millennials.

“If we have far higher proportions of pensioners renting in years to come this is going to put a far higher cost on the state to support them through things like housing benefit – this is an individual and collective problem,” she said.

She also said there were other knock-on impacts, for example young people with unsecured debt were much less likely to take risks in the labour market.

First appeared at BBC