How Women Won a Leading Role in China’s Venture Capital Industry

By Shai Oster and Selina Wang for Bloomberg

Women launch more than half of all new Internet companies in China.

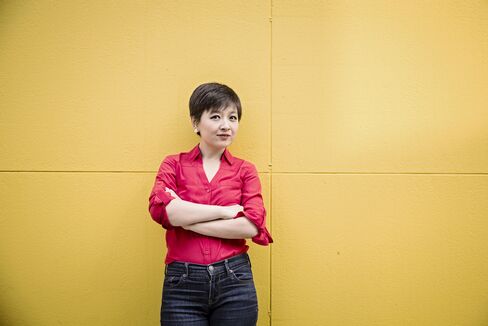

The largest venture capital fund ever raised by a woman isn’t in Silicon Valley or even the U.S. It’s in Beijing and is run by a former librarian who keeps such a low profile that she’s a mystery in her native China. Chen Xiaohong rarely attends industry conferences or events. She hadn’t given a media interview in more than a decade until agreeing to break her silence this summer. “I don’t like being part of a club,” said Chen during a four-hour discussion at her firm’s headquarters. “I believe in staying independent, making your own decisions.”

Chen, 46, is part of an unusual group of female investors who have risen to the top of the venture business in China and helped fuel the country’s technology boom. They’ve backed some of China’s most successful startups and their influence is growing as they raise more money, recruit other women and seed the next generation of technology companies.

Chen and her peers have become part of the mainstream in China in a way that’s proven elusive in the U.S. American venture firms have faced accusations of sexism and discrimination for years, including in an unsuccessful lawsuit filed by a female partner against storied Kleiner Perkins Caufield & Byers. Despite the criticism, the firms have made little progress in promoting women. Among the top U.S. venture firms, women make up about 10 percent of the investing partners and only half of the firms have any women of that rank. China is already more balanced: About 17 percent of investing partners are female and 80 percent have at least one woman.

An increasing number, like Chen, lead their firms. Kathy Xu is founder of Shanghai’s Capital Today Group, which has $1.2 billion under management and was an early backer of the e-commerce company JD.com Inc. Anna Fang is CEO of ZhenFund, one of the most influential angel investors in China. Ruby Lu, Chen’s partner at her firm H Capital until this month, previously co-founded the China business for DCM Ventures.

Their success is bringing more women into China’s technology industry. The Chinese government estimates females found 55 percent of new Internet companies and more than a quarter of all entrepreneurs are women. In the U.S., only 22 percent of startups have one or more women on their founding teams, according to research by Vivek Wadhwa and Farai Chideya for their book‘Innovating Women: The Changing Face of Technology.’

Chen and her colleagues are building on a tradition of opportunity for women in China that dates back to before the days when Mao Zedong declared they held up “half the sky.” Women worked out of necessity in fields and factories when the country was poor, and fought alongside men during the country’s civil war. By comparison, collaborating in an office is simple. Lu’s mother, who served in the People’s Liberation Army, laughed when she heard about her daughter’s diversity training at Goldman Sachs Group Inc. “She said ‘That’s ridiculous. What’s your job got to do with women or men?’ ”

The country is hardly free from discrimination. Men still hold most positions of power in politics and business, and there’s plenty of crude sexism in technology. But China has quietly become one of the best places in the world for women venture capitalists and entrepreneurs. Chen raised a new $500 million fund, the biggest ever by a woman, according to Preqin, and increased her assets under management to about $1 billion. The largest women-led fund in the U.S. was about half that size, according to Preqin’s data.

“China is fundamentally different,” said Gary Rieschel, an American who founded the China-based Qiming Venture Partners, where four of the nine investing partners are female. “The venture capital industry in the U.S. has been a private men’s club. It has been much more of a meritocracy for women in China.”

H Capital is based in a modern tower in the northeast corner of Beijing overlooking the new diplomatic district. The airy offices have wood floors and white brick walls, and a more casual vibe than the firms on Sand Hill Road in Silicon Valley. One wall is decorated with a framed charcoal drawing of a menacing-looking robot by one of Chen’s children.

Chen agreed to an interview after prodding from Lu, her former partner. Despite Chen’s penchant for privacy, Lu argued that women have the best chance to excel by helping each other and sharing experiences of victory and defeat. They sank into brightly colored bean bag chairs, where the partners usually meet with entrepreneurs and investors, and talked over fresh-cut watermelon and mineral water. “I like to bring everyone down to floor level,” joked Lu.

Chen was hardly destined for greatness. She grew up in Hubei Province, in a city famous for its gymnasts. Her parents, a high school teacher and an accountant, were neither rich nor politically connected. She was nonetheless a gifted student who got into China’s top university and won a rare full scholarship for graduate school in America, the chance for a better life.

She nearly blew it. Lonely and homesick, she abandoned the prestigious grant to join Chinese friends at Rutgers University in New Jersey. The only course available was in library science, so she studied to be a librarian. “In my heart, I knew I wouldn’t be an academic,” Chen said.

After finishing her degree, Chen answered a help wanted ad in the New York Times for a librarian at the New York media merchant bank Veronis Suhler Stevenson LLC in 1994. She got the job and in those early Internet days she managed file cabinets full of corporate records. Her meticulous company reports soon drew the attention of CEO John Suhler. “She added new meaning to the word diligent and to the words due diligence,” said Suhler. “She was better than any of our MBA associates.”

Chen was called XC because her colleagues didn’t understand the order of Chinese names and she was reticent to correct them. Suhler eventually promoted her to work on deals. “He kept sending me requests after he’d read a clip in the paper,” Chen said. She was the only Chinese woman at the firm.

Chen gained confidence as she gained experience. She worked on some 45 publishing and education deals, and was promoted again, this time to managing director.

She met Tiger Global founder Chase Coleman in 2003 through mutual connections. He originally recruited her to work at a Chinese e-commerce company he had invested in called Joyo.com. It turned out that Joyo.com’s CEO was her old high school classmate Lei Jun, who would later become one of the most successful entrepreneurs in Asia as founder of Xiaomi Corp. She returned to China in February 2004 to help the company raise money, but the plans changed when the board decided to sell to Amazon.com Inc.

Still, Coleman saw Chen’s potential. They began discussions for her to launch an investment fund specializing in education. Even before she was formally hired, she hit the road to meet with about 70 companies. In October 2004, she officially joined Tiger.

It was an opportune time. China under Communist rule had shunned capitalist practices like private business and Wall Street-style finance. But Deng Xiaopingled a wave of market reforms in the 1980s and with the dot-com boom at the turn of the century, entrepreneurs and venture investors were scrambling to make their fortunes. Few Chinese had been trained in finance, men or women, so the field was wide open for Chen and her peers. “When China got going, there just weren’t that many people,” said Qiming’s Rieschel.

One of Chen’s first investments in 2004 was in New Oriental Education & Technology Group, a provider of test preparation and foreign language courses that was looking to expand. Chen’s college English professor helped start the company and she saw the prospects for private education in China. “My whole generation was basically mentored by New Oriental,” she said. New Oriental went public in 2006 and the shares quadrupled in a year. She had made her first fortune at Tiger.

“Xiaohong is a terrific investor,” said Coleman in an e-mail. “Her capacity to navigate the Chinese investment landscape and its many nuances is second to none.”

She also invested in JD.com when it was an upstart in the shadow of Alibaba Group Holding Ltd. Sensing the company’s margins could grow sharply if they reached a large enough scale, she agreed to a valuation that surprised the tech community. “Everyone thought we were crazy, everyone thought they would die,” she said. “When we looked at it we saw only potential. E-commerce is a pure economies of scale game.”

Through it all, she raised three children. Her work habits would have been unusual, if not unacceptable, in the West. She brought her first-born son to the office every day for three years. She didn’t have a nanny or a helper so he came to virtually every meeting she had, crawling on conference tables and scribbling on walls.

She says that bringing her children helped build a bond with many of the entrepreneurs she backed. Her son did cry and disrupt meetings, but that didn’t stop her. It gave her a chance to develop a more personal relationship with founders.

She thinks being a woman gave her another advantage: It was easier for her to tell an entrepreneur he was wrong than a male investor. “It’s very politically incorrect to say this, but as a woman I can say things, they do show a special respect for women. Because it’s seen as motherly, you can be much more stern.”

Chen has set an example that’s made an impact on younger generations. “For me, there were many role models, which was helpful when I started a family and was worried about how to manage being a mom and running a fund,” said Fang of ZhenFund. Fang points to Chen as one of the models that convinced her she could balance the rigorous demands of her job with the role of being a mother.

Now, as these women rise through the ranks of venture capital and private equity, they are working to make sure more can follow in their footsteps. Fang’s nine-member investment team has four women and they’ve put money into more than 30 startups founded or co-founded by women. She is part of a group of more than 150 young female venture capitalists on a WeChat social messaging group. She’s also the only woman on a five-person panel judging startups on “I’m a Unicorn,” China’s version of the television show “Shark Tank.”

Sally Shan, former head of Asia Pacific technology investment banking at JPMorgan & Chase Co., is now managing director of the $37 billion HarbourVest Partners and runs a college mentoring program to encourage female entrepreneurs. Lu, who’s known Shan from her banker days, is a frequent lecturer there. “We’re building a community,” said Lu. “From the upstream limited partners, endowment world, family offices, to the general partners, there’s a lot of females in China that are extremely competent.”

Sexism still seeps into the industry. Chinese technology companies have made a habit of inviting Japanese porn stars to corporate events. One local Internet company hired cheerleaders to provide programmers with extra motivation. Men also lead the biggest venture firms and hold the vast majority of partnership posts, even if it is less than in the U.S. “It’s dangerous to say the field is completely even, because especially in tech, at least at the operational level, there is a huge gender issue,” said Rui Ma, partner for 500 Startups, a Silicon Valley-based fund. She often finds herself the only women at industry panels. “I also have had friends who are female and who are single who are aspiring founders who have been rejected for funding on the basis of their gender, and been told so point blank.”

Back at H Capital’s headquarters in Beijing, where Chen seems to relish spending hours in bean bag chairs thinking and talking, she admits her own views on women have evolved. She used to believe women didn’t have the broad vision for greatness that defines outstanding entrepreneurs. Not anymore. “Today, there are more and more female entrepreneurs that have totally changed my view,” she said. “They have great vision.”

First appeared at Bloomberg