It’s Not Creepy, It’s the Future

By Jason Zweig for WSJ

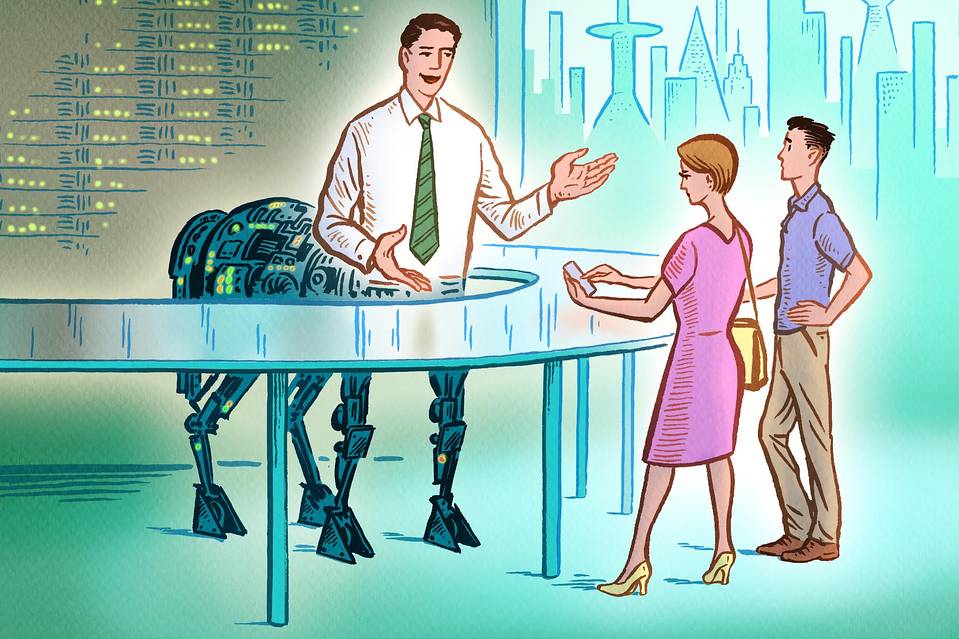

Your next financial adviser might be a centaur — not half-human, half-horse, but half-human, half-machine.

You might have heard of centaurs in chess, where a person and a computer form a team that together can beat the best human or computer playing alone. The idea, popularized after IBM’s computer Deep Blue learned chess well enough to defeat world champion Garry Kasparov in 2003, is infiltrating financial planning.

In artificial intelligence or machine learning, computers effectively program themselves to analyze data and solve problems. That’s how IBM’s Watson beat champions Ken Jennings and Brad Rutter on the television quiz show Jeopardy in 2011. And it could help make financial-planning advice cheaper, more reliable and more widely available.

In chess, a centaur is better than either the human or the computer alone because “the human and the computer have complementary strengths and weaknesses,” machine-learning researcher Pedro Domingos of the University of Washington has said.

A human financial adviser can comprehensively understand a client’s situation, moods, goals and dreams, but a computer can manage more data than any person possibly can.

Here, machine learning isn’t about picking stocks, but about predicting human behavior.

Backed by artificial intelligence, a human adviser should be better able to prevent a change in emotions or circumstances from knocking you off track to meet your goals.

Your adviser can listen for stress or fear in your voice — but only if you happen to talk to her on a given day. A computer can parse your emails and social-media posts to learn whether your use of particular words foretells changes in what you do with your money.

It can trawl through your actions — saving, borrowing, spending, prepaying a mortgage, buying a car, trading stocks and so on — to see how they correlated to economic conditions, news headlines or changes in your family situation. The computer can then attempt to predict how you will react in a similar combination of circumstances.

All this might sound like fodder for a dystopian novel by George Orwell or Philip K. Dick. But financial companies already know a ton about you. “The point is not to be creepy, but to better serve your needs,” says Brian Walter, who heads the wealth-management initiative at IBM’s Watson Group in New York.

Analyzing your past financial actions, a computer could pick up on subtly interacting variables that help “predict when you might engage in dangerous behavior and which recommendations you are most likely to implement, rather than just listen to,” says Daniel Egan, director of behavioral finance and investing at Betterment, the New York-based online investment adviser that manages $5.8 billion.

A spokesman for Vanguard Group, which manages $3.8 trillion and has $41 billion in its largely automated, online Personal Advisor Services unit, says the firm is “exploring a range of possible artificial-intelligence and machine-learning enhancements” to serve individual clients better.

IBM’s Brian Walter says the technology is being used by a “steadily growing number” of firms offering financial planning. Among other uses, advisers are applying artificial intelligence to pick up on signals that clients may be dissatisfied and to detect major changes in life circumstances that people might not mention in conversation.

Adam Nash, chief executive of Wealthfront, the Palo Alto, Calif.-based online investment adviser, says his firm doesn’t have an exact timetable but is “moving in the direction” of using artificial intelligence to improve its advice.

Financial planning has traditionally been based largely on “conversations, anecdotes and stories instead of data,” says Mr. Nash.

“It’s one thing for me to ask you what you think your savings rate is,” he says, “and another to look at your bank account and tell you what it is and what causes it to change over time.”

Other firms, including Atlanta-based online financial adviser Wela, Total Alignment Wealth Advisors of New York and McLean Asset Management Corp. in McLean, Va., are exploring how to use artificial intelligence to improve clients’ outcomes.

Machine learning could also help spread the benefits of financial advice more evenly. A human adviser in isolation, handling hundreds of clients, might neglect your needs in favor of people with more money or the squeaky wheels who crave the most attention; observing that, the computer could automatically bump you up on your adviser’s list of priorities. “Advice is going to be democratized,” says Mr. Walter of IBM.

Above all, artificial intelligence should enable human advisers to spend more time at what they excel at — understanding the personal aspects of their clients’ financial lives and building a bond of trust. Meanwhile, the computer side of the centaur should cut the cost of organizing data, analyzing choices and delivering advice.

What many advisers view as a threat seems much more likely to leave almost everyone better off. You shouldn’t need Watson to tell you that.

First appeared at WSJ