Why Fintech Startups Might Not Want to Become Unicorns

By July Verhage for Bloomberg

In mythology, unicorn sightings are blessed events. In fintech world, they might be increasingly ill-fated.

Striving to achieve a valuation of $1 billion or more may no longer be in a start-up’s best interest, according to recent valuation trends and the venture capitalists who invest in the space. Fintech firms in particular are posing a headache for investors as rising valuations create a limbo-like state in which start-ups become too pricey for larger firms to buy, but don’t have business models that are scalable enough for a debut in the public markets.

“What you don’t want to do is get into sort of this half pregnant phase when you’re past where you’re digestible but not clearly on the trajectory for long term, self sufficiency,” said Sean Park, co-founder of venture capital firm Anthemis Group.

Funding data lends credence to these concerns, with research firm CB Insights showing second-quarter funding to venture capital-backed finch companies dropping 49 percent on a quarterly basis. High-profile troubles at LendingClub Corp., which debuted at a hefty $5.4 billion valuation in late 2015 but has since sunk to $2.1 billion, have also increased investor nervousness around the space.

This lukewarm sentiment stands in stark contrast to last year’s enthusiasm about the fintech space, as investors sought to take on the outdated technology of big banks and other financial firms as well as the new set of regulations in the aftermath of the financial crisis.

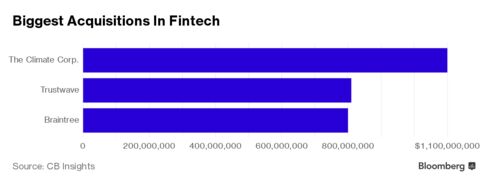

To date, CB Insights’ data also shows that the biggest acquisitions in the space have been Monsanto Co.’s 2013 purchase of agricultural insurance startup The Climate Corp. for $1.1 billion, Singapore Telecommunications’ 2015 acquisition of payment security startup Trustwave and EBay Inc.’s deal to buy global payments platform Braintree for $800 million in 2013.

Another such deal was Northwestern Mutual’s 2015 acquisition of LearnVest, an online financial planner, for what sources say was over $250 million but less than the $1 billion unicorn mark. Alexa von Tobel, the founder and CEO of the startup, says she’s still happy with her decision to get bought by an incumbent.

“In my experience, we realized the value of the opportunity faster by pairing up with these companies that have scale. I’m a year in and very happy with what we decided to do,” she said.

But a number of startups have already exceeded these valuations. Online lending platforms Social Finance Inc. and Lu.com now have valuations topping $4 billion and $18 billion, respectively, and JD.com’s finance subsidiary has a $7.1 billion valuation.

Others are right on the line. Robo advisors Betterment LLC and Wealthfront Inc. are each sitting at $700 million, and online money transfer startup WorldRemit has a valuation of $500 million.

With each increase, the pool of possible buyers gets smaller, and large corporations get more skeptical of whether these values would still allow them to achieve a good return on the investment.

“From an incumbent’s point of view, what we’ve heard from several clients is they’re less certain about acquisitions because they’re also not always as confident on the valuations that certain companies have come up with,” said Nikhil Lele at Ernst and Young LLP. “They’re trying to really understand if they are to acquire, what is the true accretive value they get by doing so and how does that map up with the valuation that’s on the table.”

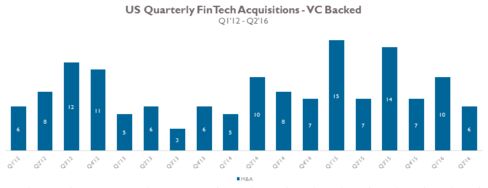

Acquisitions for fintech startups saw a big bump in 2015, but things have tapered off this year. According to CB Insights, there were 22 acquisitions in the first half of 2015, while 2016 saw that number drop to 16.

One scenario that comes up when asking who might be able to acquire some of the startups with higher valuations is the possibility of companies outside of the finance space stepping in and making acquisitions. While firms like Apple Inc. and Amazon.com Inc. have sizable war chests of cash that would allow them to go on a start-up shopping spree, they may be held back.

“We’ve been waiting for a tech company type of entrant for some time, and that’s certainly a possibility,” said Uday Singh, a partner at consultant AT Kearney Ltd. “But barriers that the tech companies have to this is that the financial services area is so highly regulated that they are not used to the compliance they would face.”

That may leave the unattractive option of being sold for a lower valuation, which has happened in a number of other industries. Gilt Groupe Holdings Inc., for instance, was once valued at about $1 billion, but later agreed to be acquired by Hudson’s Bay Co.for $250 million.

Going public also isn’t as attractive as it used to be. Of three prominent IPOs in the space, only one is trading above its initial offering price. LendingClub and On Deck Capital Inc. are both significantly below where they debuted, while shares of Square Inc. are now above that price despite a volatile few months.

Despite a rocky performance in the public market, OnDeck’s Chief Operating Officer James Hobson told conference attendees in May that he doesn’t regret the company’s decision to enter the public markets, although he cautioned it might not be the best option for everyone.

“I think it’s a discussion,” he said. “I don’t think you should just assume ‘Oh, we’re gonna go public.’ It requires a lot of work … a lot of effort … a lot of investment. But if you discuss that, it can absolutely be a great path for a lot of companies to take.”

Nauiokas of Anthemis said that while a number of startups may already be in that “half pregnant” phase, they might be fine with staying in . “I think for a lot of these companies that are in that in-between phase, there’s a lot of runway to go it alone.”

First appeared at Bloomberg